In pods we trust: enter the 700mph Hyperloop

Underground tubes carrying passengers at speeds of 700mph may sound like a pipe dream, but Richard Branson has faith in the hyperloop. By Mark Harris and Nick Rufford

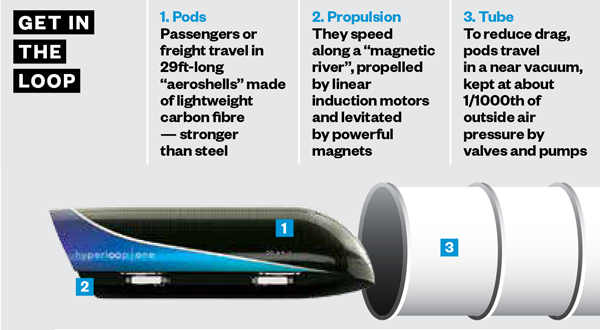

MAGNETICALLY levitated pods, powered by solar energy, blasted through tubes at almost the speed of sound and able to deliver passengers from London to Edinburgh in 45 minutes. That’s the concept behind the hyperloop, a cross between a bullet train and the old-style pneumatic tubes that conveyed mail and money around department stores.

If it seems familiar, that’s because it revives the decades-old sci-fi staple of trains travelling through tubes with the air pumped out to reduce friction. Get rid of their wheels as well, by levitating the pods with powerful magnets, and trains could travel faster still, goes the theory.

The term “hyperloop” was coined by the founder of Tesla, Elon Musk, in 2013, but he declared himself too busy to pursue the idea, inviting other engineers to step up to the challenge. The response was immediate. Students, entrepreneurs and engineers around the world started designing streamlined pods and continent-spanning tubes. Four years on, dozens of countries — including the UK — have plans for routes that could compress long trips by train or car into hyperloop journeys barely long enough to read a paper.

If you think the idea should have stayed on the pages of novels such as Robert Heinlein’s Double Star, tell that to Sir Richard Branson, who has just bought a chunk of the world’s biggest hyperloop company and renamed it Virgin Hyperloop One.

If you think the idea should have stayed on the pages of novels such as Robert Heinlein’s Double Star, tell that to Sir Richard Branson, who has just bought a chunk of the world’s biggest hyperloop company and renamed it Virgin Hyperloop One.

“We’ve been looking for technology that will transport people in Britain and other countries at much greater speeds [than on trains],” says Branson.

“The exciting thing about hyperloop is that we could — if we could get a straight line between London and Edinburgh, or London and Glasgow — transport people in about 45 minutes. The pod could literally come to your office or your home and pick you up. It would then take you down a tunnel, connect to our system and take off. [It would arrive] 45 minutes later — a lot easier than the 4½ [or] 5 hours it takes currently in trains. But obviously it’s not just for Britain. We are talking to countries all over the world.”

Virgin Hyperloop One already has a working prototype that runs on a 500-metre test track in the Nevada desert, half an hour’s drive out of Las Vegas. In July, its first-generation pod, the XP-1, accelerated for 300 metres and glided above the track using magnetic levitation (maglev), before braking and coming safely to a stop.

Until 2014, Josh Giegel, the company’s co-founder, was a rocket scientist, developing next-generation spaceships for Virgin Galactic and SpaceX. Then Musk’s hyperloop proposal got him thinking. “My mission is to demonstrate to the world that hyperloop is possible, that it isn’t just a complete crazy dream,” Giegel says. Together with the venture capitalist Shervin Pishevar, he created a start-up dedicated to building hyperloop networks.

“It’s like us building the airplane, the airport, the air traffic control . . . and the sky,” he says with a laugh. “But if you’re able to engineer those all simultaneously, you get to design something that hasn’t even been envisioned before — and you get to do it with 21st-century technology.”

“The exciting thing is that we could transport people between London and Edinburgh in about 45 minutes”

Hyperloop One has about 300 employees and — before Virgin took an undisclosed stake — had raised about £180m, with feasibility studies completed in Dubai, the UK, Russia and America. The company’s goal is to have three systems in service by 2021.

“Elon’s original idea was inspirational but we’ve moved quite a way beyond that now,” says Giegel. “Two-and-half years of simulation and development has resulted in a system that is safer and better. We’ve essentially reinvented maglev to make it much more energy efficient.”

While high-speed passenger travel remains the main objective, Giegel says hyperloops could also revolutionise freight transport.

“A hyperloop pod is something that could fit perhaps 99% of all Amazon packages,” he says. “You could put a distribution hub in the centre of the UK and transport packages the same day throughout the country. What we’re building now are Lego blocks, fundamental pieces of technology that connect and can be modularised into different vehicles for different uses.

“We’re very focused on how to make this work in the real world. A problem with mega-projects is that they take so long to build you spend a lot of money before you earn a dollar in fares. We’re developing advanced manufacturing techniques to be able to build fast.”

Giegel points out that hyperloops need far less space than traditional high-speed rail networks, generate almost no noise and there is no threat of animals or cars straying onto the track. “There are also ways to entice communities to want to have them, such as generating extra power from solar panels and making them so cheap people can ride them very often, even daily,” he adds.

Most hyperloop engineers believe that the first systems are likely to be created in the Middle East, perhaps Dubai, where tracks can be built in empty desert, there is plenty of sun to power them, money is plentiful — and regulations are not. However, European countries have been among some of the most enthusiastic supporters. Hyperloop One has had what it calls “advanced discussions” to demonstrate its technology in Holland and Finland.

Adam Anyszewski is one of those who believes the dream could become reality. He and a group of fellow students in Edinburgh University’s HypED team are looking beyond the pod itself to a fully functioning hyperloop network.

“What the Tube did for London, the hyperloop will do for the UK,” he predicts. “With Brexit, the country has to start being more competitive, increasing its productivity and having a high-quality workforce that is well integrated within the country’s infrastructure.”

“What the London Underground did for London, the hyperloop will do for the UK”

This summer, HypED’s London to Edinburgh route was named one of the winners in a global hyperloop competition. It would connect the two cities via Birmingham and Manchester, with pods hopping between them in as little as a quarter of an hour.

“Everyone hates the HS2 high-speed rail project but everyone knows it’s necessary,” says Anyszewski. “Hyperloop offers a compelling alternative: fast, cost-competitive and much more environmentally friendly than any other mode of transport.

“The UK is a very favourable environment. The responses we have had from the Treasury, the Infrastructure and Projects Authority, and the departments of international trade, transport and business have been overwhelmingly positive.”

Although the London to Edinburgh route could not run on solar power alone, the efficiency of running pods through evacuated tubes means they should use less than half the energy of trains, and up to six times less than planes, according to a US government study.

For all the enthusiasm for such sustainable, low-cost travel, however, experts remain largely sceptical. “It would be a real feat to be able to make something like the hyperloop financially viable,” says Professor Bent Flyvbjerg of Oxford University’s Saïd Business School, an economist specialising in mega-projects. “There are very few high-speed rail lines around the world, and they have all needed subsidies.”

One big problem for any UK hyperloop network would be fitting it in alongside existing roads, tracks and housing. London’s Crossrail project tipped the scales at an eye-watering £14.8bn — and that is for well-known and proven rail technology. Flyvbjerg thinks a more economical option would be to run hyperloops from out-of-town airports.

“The more you can leverage existing infrastructure, the lower the cost you can achieve,” he says. “It would be an advantage for hyperloop to have stations where people can get rid of their cars and catch a pod. Airports are that kind of place; city centres are not.”

The dream — or, for less hardy travellers, the nightmare — of commuting from London to Edinburgh in a magnetically levitating pod at about 700mph looks likely to remain, for a good while yet, just that. The practicality of long-distance vacuum tubes has yet to be proven, and the cost and regulatory challenges of building an entirely new transport network loom large. Nearly half a decade after Elon Musk dreamt up the hyperloop, it still looks almost as far off as his Martian colonies.

Sections in The Future of Transport in association with Audi:

- The co-pilot takes over The latest autonomous cars are learning road sense from the experts: us

- The ride to work Don’t be late for the office: get your rocket skates or jetpack on

- In pods we trust From London to Edinburgh in 45 minutes? Take the hyperloop

- Back in full flow Eco-jets and floating cycle paths could soon rejuvenate city rivers