In full flow — how rivers could ease road traffic

Innovations such as eco-jets and floating cycle paths could soon bring a buzz back to city rivers and ease road congestion, says Emma Smith.

FOR THOUSANDS of years, rivers were the transport arteries around which the great centres of population clustered and thrived, enabling the rapid movement of people and goods, allowing commerce to flourish.

Nowhere was this more true than London where, in its 19th-century heyday, the port of London was the busiest in the world and exotic goods would arrive by water, while thousands of small boats transported people across the Thames, amid a constant hubbub of activity.

With the rise of containerisation after the Second World War, and the move to bigger ships, the rivers lost their place as the engine rooms of a city’s prosperity.

Dockyards declined, before being transformed into inner-city marinas. The rivers lost their functional role as a means of transport.

Now, architects and inventors are hoping to restore rivers to the heart of our cities’ transport systems.

Seabubbles

High-speed, hydrofoil commuter travel

Seabubbles, a French start-up, is hoping to change the face of river transport by introducing a fleet of high-speed, environmentally friendly river taxis into cities around the world, including London.

Founded by Alain Thébault, a record-breaking yachtsman and designer, and Anders Bringdal, a Swedish former windsurfing champion, the company has developed a compact electric boat (with the look of a waterborne car — see main picture) that uses hydrofoils to lift it out of the water, reducing drag and enabling a top speed of about 25 knots (29mph) — an experience that has been compared to a “magic carpet ride”. Passengers could hail the Seabubbles with a mobile app, in a similar way to Uber.

There were plans to begin a public trial of the Seabubbles on the Seine in Paris last month but technical and regulatory issues (particularly the need to raise current speed limits on the river) have pushed the start date back to next spring.

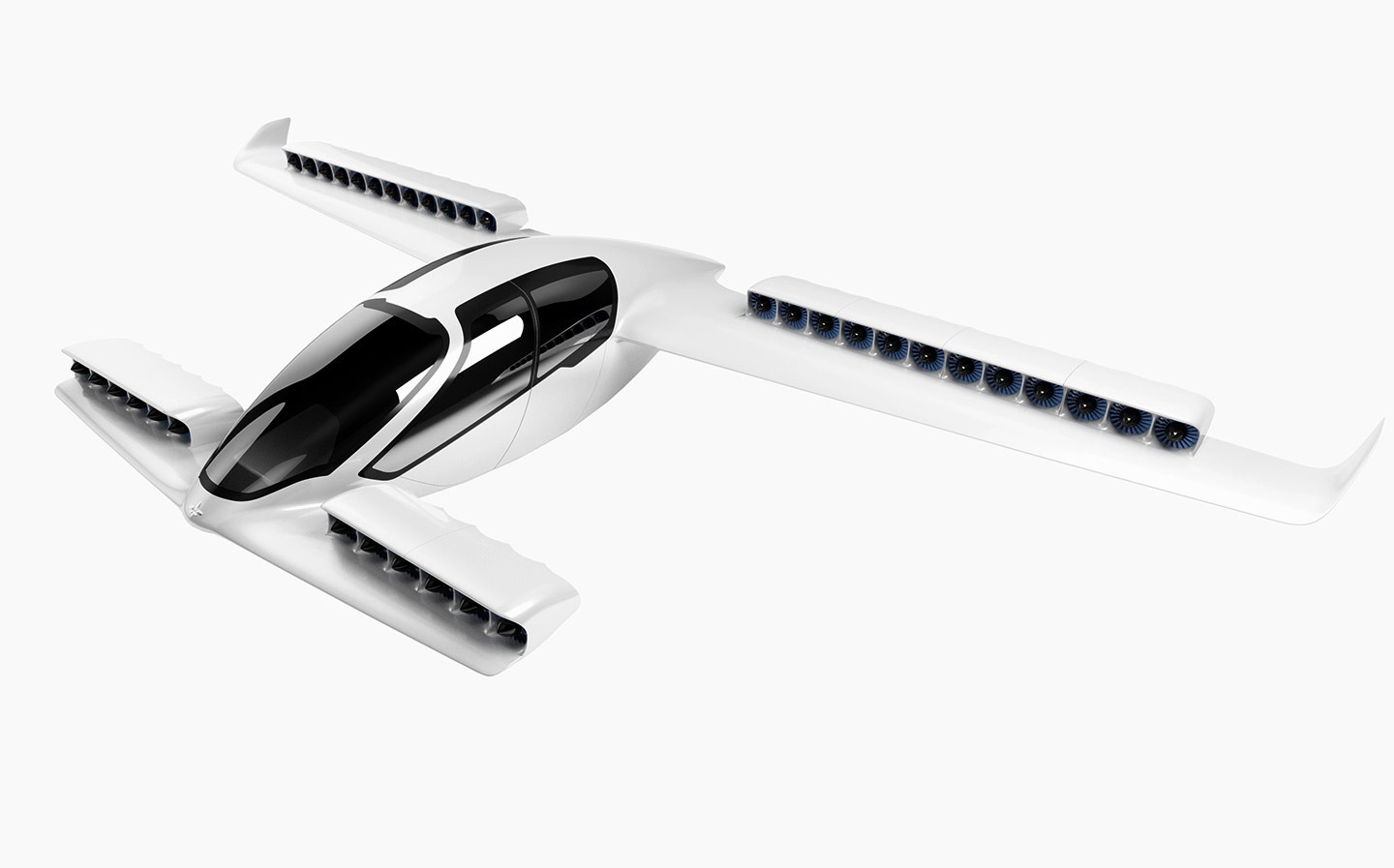

Lilium Jets

River transport meets the Jetsons

Imagine arriving at Heathrow airport, hopping into a flying taxi and setting down on a floating landing pad on the Thames, in the heart of the capital, just 10 minutes later — a journey that would take at least an hour by car.

That is the future as envisaged by Remo Gerber, chief commercial officer of Lilium, a Munich-based technology start-up that is working on a pollution-free, low-noise, electric jet capable of vertical take-off and landing, which could carry four passengers, plus pilot, and travel at speeds up to 186mph.

“Ten minutes from Heathrow to Embankment, is a conservative estimate,” says Gerber. “And [it would take] only minutes more to the City or Canary Wharf.”

The ultra-light carbon fibre jets work by way of 36 electric engines, situated under 12 flaps along the wings. The flaps start in a vertical position to give the power for take-off, then gradually tilt towards horizontal. When they have reached the completely horizontal position, all lift necessary to stay aloft is provided by the wings (as on a conventional aeroplane), enabling a range of about 186 miles between charges.

Following a successful, remote-controlled flight earlier this year, the first manned flight is planned for 2019. The first Lilium jets could then begin appearing by 2025 (“we are talking to various large cities”), with landing pads on the Thames just one of many potentially “fantastic opportunities”, says Gerber.

The Thames Deckway

A floating cycle path

The brainchild of a “space architect” and a graduate of the Royal College of Art, this 7.4-mile floating pathway would enable cyclists to travel from Battersea in southwest London or Canary Wharf in the east to the Millennium Bridge in the City (the proposed midpoint) in 15 minutes.

Anna Hill, a “social entrepreneur, innovator and artist-designer”, devised the project with David Nixon, who worked on Nasa’s crew quarters for the International Space Station, after the pair met while working at the European Space Agency. “I had been living in the Netherlands, where cycling was a pleasurable way to get to work, and then I returned to London, and became aware of the pressing danger issues of congestion and pollution for cyclists and walkers,” says Hill.

The Deckway, which includes the engineering giant Arup among its backers, would be designed to fall and rise gently with the tides and generate its own energy (for lighting, refreshment kiosks and so on), from a mixture of renewable sources (solar, tidal and wind).

The current plan is to charge a toll of £1.50 to use the floating pathway which, if given the green light, would cost in the region of £600m. Construction is scheduled to begin on a small demonstration section, in east London, in 2018.

The River Thames Monorail

One track mind

What feature about future transport would be complete without a monorail? But Richard Horden, the architect behind the scheme, insists this is no flight of fancy, but an attempt to address London’s transport issues and reconnect commuters with the sights of their city.

“Imagine a slim, silver, sliver of a train, with a glass roof — futuristic and elegant,” says Horden.

The rail — “ideally a maglev [magnetic levitation] system with the train floating just above the rails” — would run along the banks of the river, underneath the southern arches of the central London bridges.

“I constantly revisit this project because I cannot understand why on earth it wasn’t built,” says Horden, who first envisaged the scheme in 1995. “It is a wonderful possibility. Now, you disappear underground into the Tube — with the monorail, you would be able to see the landmarks.”

Sections in The Future of Transport in association with Audi:

- The co-pilot takes over The latest autonomous cars are learning road sense from the experts: us

- The ride to work Don’t be late for the office: get your rocket skates or jetpack on

- In pods we trust From London to Edinburgh in 45 minutes? Take the hyperloop

- Back in full flow Eco-jets and floating cycle paths could soon rejuvenate city rivers