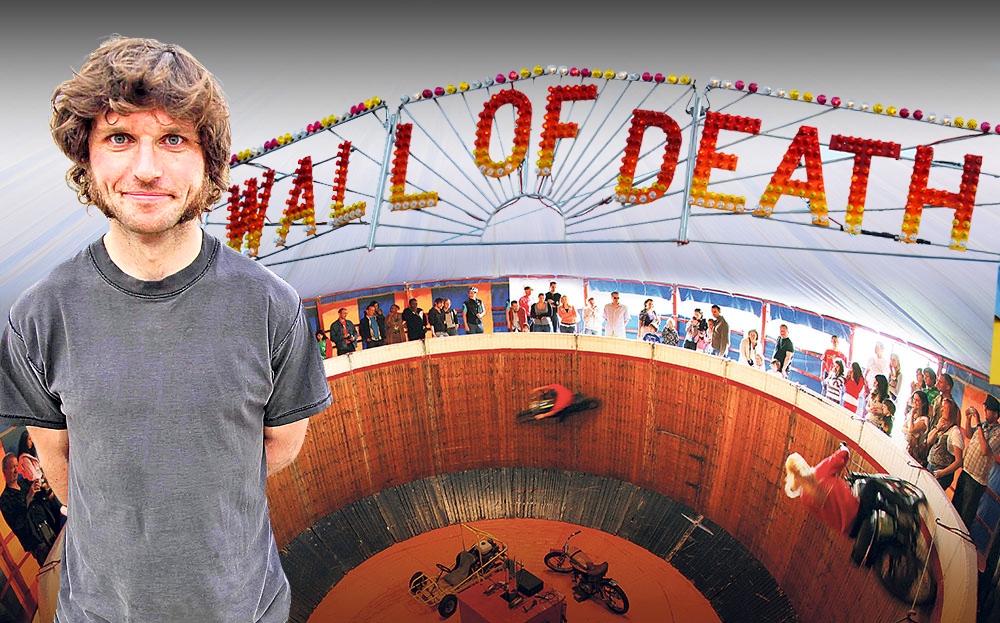

The wall of death: Guy Martin's biggest challenge yet

The G-force had better be with me — or I‘m hitting the roof

DAFT THINGS started to happen when all the Jeremy Clarkson stuff kicked off and it became clear he was getting the boot from Top Gear. Loads of rumours started that I was going to replace him.

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

It was all a load of rubbish at first — just bookies putting out odds to get gullible people to part with their money — but then Chris Evans got involved with Top Gear and Andy Spellman, my manager, got a phone call from some gadgie at the BBC saying that Evans wanted to talk to me and that I could do one show, do all the shows, do what I wanted, as long as I was in Top Gear.

I didn’t say no straight away, but the more I thought about it, the more I knew it wasn’t right for me. For one thing, if I did it, I’d always be compared with Clarkson. Another reason not to do it was because the BBC man said it was the biggest television show in the world.

How many presenters would turn that down? Not many, but I did. I’m not being cocky, but I can turn down the biggest TV show in the world because TV work is not my big picture. I sometimes whinge about the amount of attention I’m getting at the moment — imagine how bad it would be if I were on Top Gear. I couldn’t go and race a Harley-Davidson chopper at Dirt Quake on a quiet weekend, could I?

Top Gear might pay squillions of pounds, but what do I want all that for? I can earn enough for the life I want fixing lorries and doing a few other bits and pieces. In any case, we’re doing our own thing and North One Television is on our wavelength now. It’s the only production company I’ve worked with, and it’s come up with its best idea. It’s the best idea anyone’s come up with — the wall of death.

The different walls would try to outdo each other with dafter ideas until one show had an adult male lion in a sidecar

I’ve done a lot of interesting stuff in the process of filming the Speed with Guy Martin television shows, but some of it has been a bit dangerous. Cycling blind at 112mph on a beach, in the slipstream of a racing lorry, got the heart pumping. Flipping that racing hovercraft could have been messy. Nosediving a Suzuki 450cc motocrosser into a Welsh lake knocked the stuffing out of me. I also crashed a sledge at 80-odd miles an hour.

But it all sounds a bit “so what?” compared with the next challenge. The idea is to set the highest speed yet recorded on a wall of death.

This popular fairground attraction dates back to the early years of the 20th century. Motorbikes had hardly even proved themselves on the dirt roads of the day before folk were building huge wooden barrels to ride around, defying death on the vertical sides of the walls, stuck on by centrifugal force. The wall of death looked amazing then and it still does today.

There used to be dozens of them in America and Britain, some set up permanently at seaside resorts, while others would travel to shows. The different walls would try to outdo each other with dafter ideas until one show had an adult male lion in a sidecar. Not many walls remain now, just a handful in Europe and America.

Probably the most famous show still working is the Ken Fox Wall of Death, which I saw at the bike show in Spalding, Lincolnshire, a few years back. The display lasts about 15 minutes, costs a couple of quid to get in and the family have been touring since 1995. The crowd stands around the top of the wall, under a big-top-type tent, looking down on the wall and the riders below. It’s mega.

The original idea was for me to attempt 100mph on a wall of death — more than three times as fast as anyone reaches on the world’s remaining walls — but when the researchers looked into it they reckoned that would be impossible, because I would have to be pulling 10g to do that: 10 times the force of gravity.

Under 10g a bloke who has a mass of 11 stone — about what I am — weighs 110 stone. That’s because mass is constant, but weight is relative to gravity. If you were on the moon, where the gravity is about one-sixth of what it is on Earth, you could pick up something that you could never shift on this planet, but its mass is exactly the same.

The original idea was for me to attempt 100mph on a wall of death but that would be impossible…I would have to be pulling 10g to do that: 10 times the force of gravity

A human head, which makes up about 8% of the mass of an adult, in my case would weigh about 12lb if you chopped it off and put it on a kitchen scale (but just take my word for it). At 10g my neck muscles would be trying to hold up 8½ stone — 119lb — of head, plus the 33lb or more of helmet.

But that’s not the main problem; it’s the fact that the G-force is too much for the human body’s circulation system and the heart isn’t strong enough to pump enough blood to the brain. The blood concentrates in the lower half of the body and that causes blackouts and G-Loc — G-force-induced loss of consciousness.

It was decided — I can’t remember who by — that I could probably cope with 8g at the very most, and that equates to a speed of about 80mph. Still, the chances of blacking out and losing consciousness are high. And to even attempt that speed, we’d need to build the biggest wall of death yet made.

Hugh Hunt, an Aussie academic at Cambridge University, worked out the necessary diameter to be 120ft. Ken Fox’s wall of death — the one I saw at the bike show — is 32ft across and he rides it at speeds of 25mph-30mph.

To put the wind up me, before I even started to be taught how to ride, I sat on the handlebars of Ken’s Indian Scout bike while he set off and rode the wall. He was dressed in his jeans and trainers, as if he was off to walk the dog, and so was I.

Everything was a total blur to me and then I started to feel sick. Ken told me to wave but because of the G-force I couldn’t lift my hand up — I was just glued in place.

Then it was my turn. Lesson No 1 was me sitting on the bike being pushed around on the flat base inside the wall, with the engine running but in neutral so I got used to the noise of the bike. Even that made me dizzy. Next, I rode around the bottom, completely on the flat, and after that I was so dizzy the boys had to hold me up when I stopped. I’d sit down for five minutes and try again.

By the end of the first day I’d only got halfway up the track, the 45-degree slope. I didn’t know if that was good or not, compared with other learners. It didn’t feel too good.

Late that night I drove back to the hotel and sat on the bed thinking things through. I had arrived at the Foxes’ yard in the morning believing: I can do this. Then after riding on Ken’s handlebars, all I could think was: “Bloody hell!”

When I started going round in tight circles, even at walking pace, I was so dizzy that I felt the chances of me riding on the wall were even worse. I couldn’t even ride on the track at the bottom. These two days were dead important, because if I didn’t get to grips with riding on the wall, the whole thing that had been planned would be off.

As I sat on my bed, I was fascinated by how my body was working. I’d felt so dizzy I couldn’t stand, but then the brain started working out the maths of the situation and decided: “Right, we need to do this, this and this.” I don’t know what was happening, but my brain was working out how to deal with it.

At the start of the second day I had the confidence that my brain was cleverer than I was. I’d do a run of five laps, stop, sit and talk about it, run again, then go outside: fresh air, cup of tea. Then back in again and aim to go a bit faster and a bit higher for another five laps.

Even 25mph–30mph feels fast in a 32ft wooden drum, but it’s bugger all compared with the speed I’m going to attempt. Ken said they can get to 40mph on their wall but at that speed they are at the point of blacking out from the G-force starving the brain of blood.

This is what happens when you black out: your vision goes grey, then you get tunnel vision, when you lose peripheral vision, then you lose vision totally — that’s the blackout — and finally you lose consciousness

This is what happens when you black out: your vision goes grey, then you get tunnel vision, when you lose peripheral vision, then you lose vision totally — that’s the blackout — and finally you lose consciousness. It can happen quickly and I’ve got to learn where the point is. I need to learn what it feels like to very nearly black out and come back again.

If I do black out, it can go one way or the other. I can collapse on the handlebars, let off the throttle and crash into the bottom. Then it’s a case of straightening everything out, dusting myself down and going again. But the other way is I pass out, keep hold of the throttle, go out of the top at more than 80mph and into the rafters. Which is likely to kill me. I don’t need to be doing that. I need to learn: right, I’m blacking out; tense up, back off.

There was talk of me wearing a G-suit, like fighter pilots wear. These compress the body to help deal with slightly higher G-forces for longer. It’s not a magic bullet and at the time of writing it’s been decided there isn’t a lot of point in using it, so I’ve got some serious acclimatising to do.

Plus I don’t just want to be the fastest ever rider on the wall of death — I want to do it on a bike I’ve built myself. It’s an old Triumph triple engine in a Rob North replica racing frame, a bike like my dad owns.

It’s more important for me to build this bike for the wall of death than for me to spend time preparing a bike for the Isle of Man TT or a TV show or anything like that, because I really believe nothing else I’ve done in life can compare with this attempt.

Even after the speeds I’ve been at in the TT and the Ulster Grand Prix, and now with the little bit of experience I’ve had actually riding a wall of death, I still can’t imagine what it’s going to be like. And I have the added problem of trying to fit in the training, plus build a one-off bike, in what is turning out to be the busiest year of my life.

Extracted from When You Dead, You Dead by Guy Martin, published by Virgin Books on October 22 at £20

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk