Sir Clive Sinclair, inventor of the C5 pedal-electric car, dead at 81

Sinclair had more success away from motoring

SIR CLIVE Sinclair, the inventor of the C5 pedal-electric car and the world’s first pocket calculator, has died aged 81.

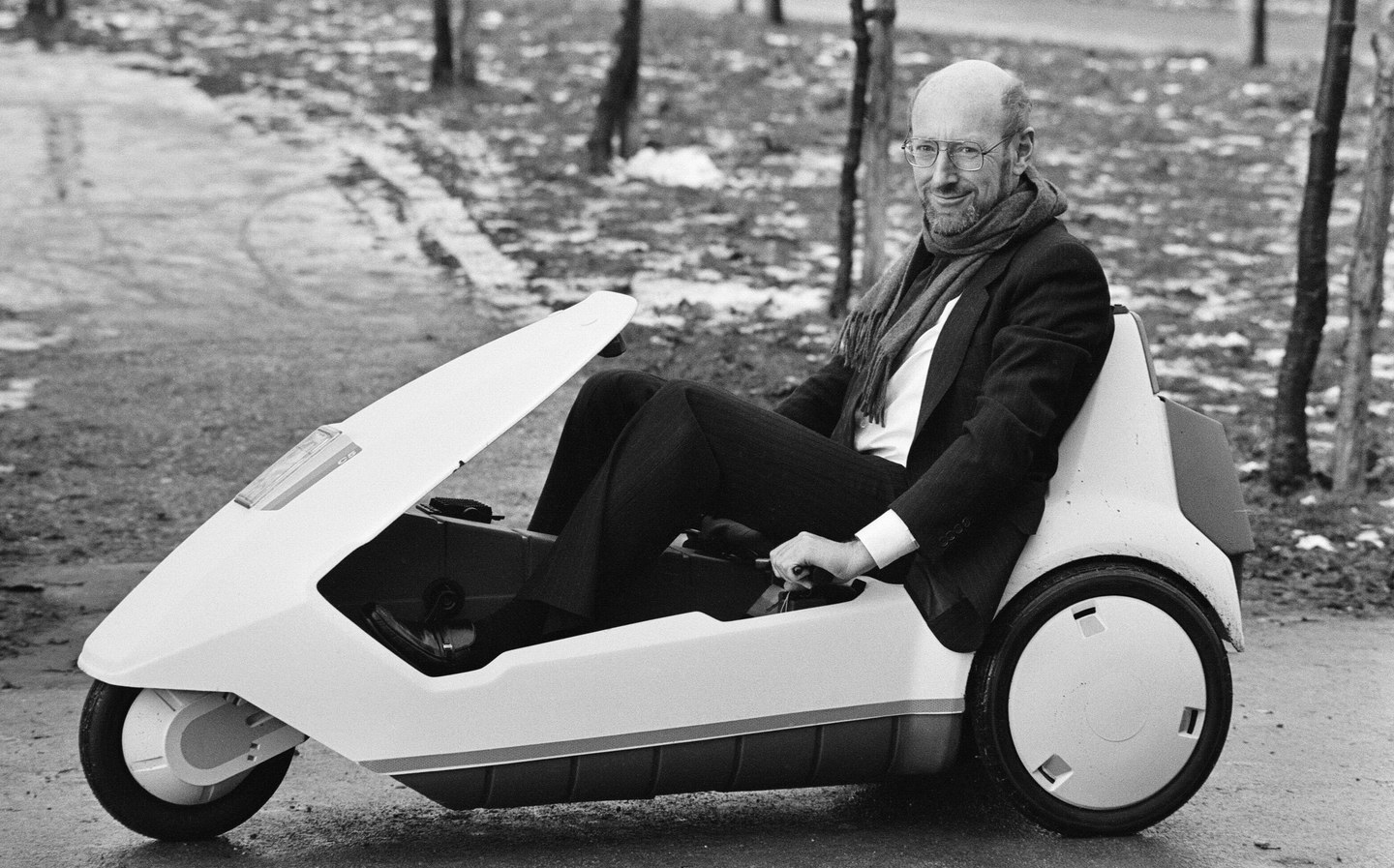

Although recognised as a computing pioneer who helped bring cheaper personal computers to the wider British public, Sinclair was also known as the brain behind the ill-fated Sinclair C5, a pedal-electric vehicle that became a byword for business and marketing failure, but was perhaps ahead of its time.

Clive Sinclair was born in Surrey in 1940 and, while he taking A-levels in physics, pure maths and applied maths, he began sketching designs for miniature transistor radios in his exercise books. Instead of attending university, Sinclair decided to pursue his electronics hobby, producing a self-assembly kit for a micro-radio and writing several books on the topic.

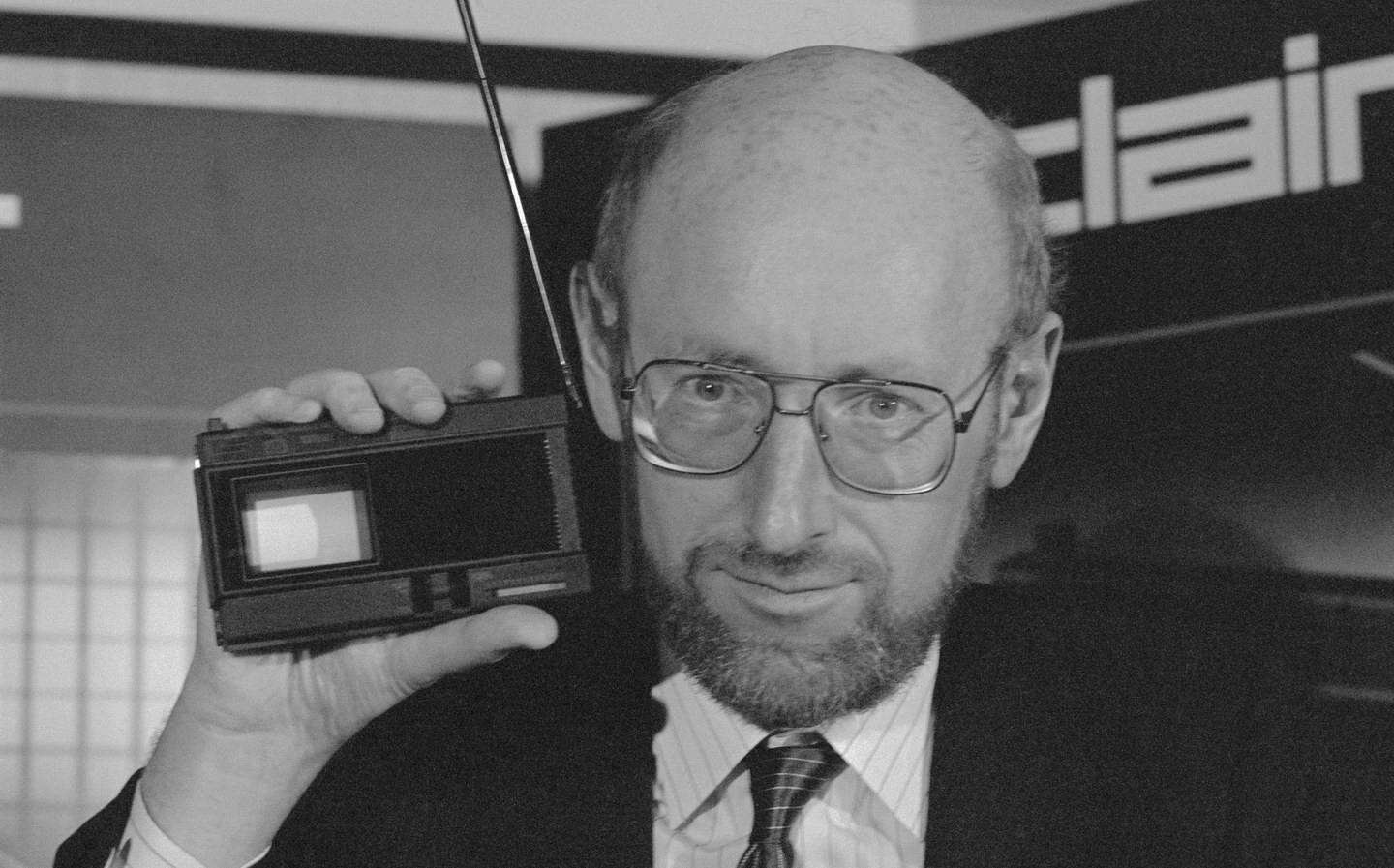

In 1961, he founded Sinclair Radionics, which by the early 1970s was producing a range of products including the Sinclair Executive, the world’s first slimline pocket calculator and the first calculator to be mass-produced. Launched in 1972, the Executive was a great success for Sinclair making a healthy profit.

One of the company’s other products, however, was a portent of things to come.

The Black Watch, which debuted in 1975, was a digital wristwatch with extremely sensitive integrated circuitry that made it too fragile and unreliable. Despite batteries advertised as having a one-year lifespan, in many cases the Black Watch’s batteries barely lasted ten days and were difficult to replace. The display was hard to read and even its time-keeping ability was poor.

These design flaws and the subsequent number of watches returned for replacement or repair were a disaster for Sinclair Radionics, which would have gone bankrupt were it not for a government bailout.

With the National Enterprise Board (NEB) taking a 43% stake in Sinclair Radionics in 1976, Sinclair’s relationship with the board and his own company worsened as the NEB began selling off parts of the business from which Sinclair soon departed.

Now at the helm of another electronics company, Science of Cambridge, which he co-founded in 1977, Sinclair became interested in the newly emerging field of microprocessors and the company began producing the MK14, a computer available in kit form costing £39.95.

Although the MK14 was successful, following the acrimonious departure of his partners in Science of Cambridge to found Acorn Computers, Sinclair decided to further pursue the model of the low-cost personal computer.

In 1980, the company launched the Sinclair ZX80, available in kit form for £79.95 or fully built for £99.95. The ZX80 was an immediate success for Sinclair who renamed the company Sinclair Computers and, later, Sinclair Research.

Despite losing out to rival Acorn for a BBC contract to teach viewers about computers, Sinclair followed up the ZX80 with the cheaper ZX81, which was huge hit, becoming one of the best-selling computers in the UK and United States. The ZX Spectrum, with its colour display was another success for Sinclair and the company turned a healthy profit, helping make Sinclair a millionaire. He was awarded a knighthood in 1983.

The birth of the Sinclair C5

Sir Clive, as he now was, had long nursed an interest in electric vehicles and, in 1983 sold some of his shares in Sinclair Research to capitalise a new venture, Sinclair Vehicles.

The company began working on a design for an electrified one-person vehicle that would use lead-acid batteries to propel it to 30mph with a range of 30 miles; a figure, according to Sinclair’s research, well in excess of the average daily commute of both car drivers and scooter or moped riders, both of which methods he wanted to supplant with this new invention.

Named the C1 — the “C” standing for Clive — the vehicle was to be safer, more spacious and more weatherproof than a bicycle or moped, cost £500 and be simply engineered with a body created from injection-moulded plastic. To reduce costs, Sinclair opted to rely on existing battery technology then in use on milk-floats, rather than invest heavily in expensive research and development on new batteries.

Crucially, thanks to new legislation passed in 1983, prompted by bicycle manufacturers who wanted to begin selling electric bikes, Sinclair’s new vehicle could be driven without either a licence or helmet by anyone over 14 years old, though the speed would have to be limited to 15mph, weight to 60kg and motor to a 250W output.

Sinclair did not conduct any market research, believing instead that the C1 would create its own market much like his personal computers did.

Sinclair entrusted design work to Ogle Design, which had previously created the Bond Bug microcar, the Reliant Scimitar and Robin, the Mini-based Ogle SX1000 coupé and, for George Lucas’s Star Wars films, the Landspeeder craft.

Ogle’s design became known as the C5, and further improvements came with the addition of handlebars rather than a steering wheel, which made ingress and egress from the C5 safer and easier, according to Tony Wood Rogers, a designer on the C5 project and long-time collaborator with Sinclair.

Lotus Cars undertook some engineering work on the C5’s chassis and a 23-year-old industrial designer, Gus Desbarats, was brought in to refine the design and styling of the polypropylene shell. He later described his contribution as “converting an ugly pointless device into a prettier, safer and more usable pointless device,” partially with the addition of a rear-mounted mast to allow for greater visibility to other road users.

The electric motor was produced by an Italian firm, Polymotor, using a design derived, not from a washing machine as is often erroneously claimed, but from the motor for a lorry engine cooling fan.

While testing took place over 19 months in great secrecy, a deal was struck by the Welsh Development Agency to produce the Sinclair C5 in Hoover’s washing machine plant in the economically depressed south Wales town of Merthyr Tydfil.

Initial sales were projected by Sinclair to be in the region of 200,000 per year, rising to 500,000, figures that no doubt looked attractive to Hoover.

The Sinclair C5’s reception

The C5’s launch at London’s Alexandra Palace in January 1985 was disastrous.

Invited journalists found the pedal-electric vehicle to be unreliable with the motor frequently overheating; the C5’s batteries ran down after just seven minutes and it was not able to negotiate the slight snow- and ice-covered roads around Alexandra Palace. It was heavy to operate by pedalling alone — something users found themselves having to do all-too-often — and due to its height, exhaust fumes from other traffic blew straight into the driver’s face.

In addition, the batteries suffered noticeable range depletion due to the cold, the motor barely coped with ordinary hills, let alone snowy ones, and most observers expressed grave concerns about the C5’s safety in use.

The public’s response was muted too. Sinclair sold fewer than 200 C5s at the Alexandra Palace event, though within four weeks some 5,000 had been ordered with mail-order forms having been sent out to all Sinclair computer customers.

Famous owners included princes William and Harry, Elton John and that other notable British futurist, the sci-fi novelist Arthur C. Clarke.

To keep the price at under the £400 mark, the C5 was sold with accessories such as indicators, weatherproofing, mirrors, mudflaps, a horn and the high-vis mast as optional extras.

In real-world use, the C5 was found to be too slow with the batteries usually delivering much less than their promised 20 miles of range. Production was soon cut back to just 100 per week, down from an initial 1,000, due to the lacklustre demand. Security was another concern with thieves able to pick up a C5 and simply carry it away.

Sir Clive Sinclair’s legacy

Although it attracted some positive press for its handling and ease of use, sales of the C5 remained low and unsold stock began piling up. Production ceased in August 1985, and Sinclair Vehicles had totally collapsed by October. By the end of 1985, retailers were offering the C5 for £139.99 including a full set of accessories.

The C5 debacle put paid to Sinclair’s plans for a full range of electric vehicles, eventually incorporating a full-sized saloon.

In the few years after the launch, however, the C5 developed something of a cult following and unsold vehicles that had been snapped-up at discount prices sold for far more than their original price.

After the C5, Clive Sinclair sold most of Sinclair Research to Amstrad, owned by Alan Sugar. Lord Sugar described Sinclair on Twitter this week as a “good friend and rival”.

Sinclair focused the efforts of the slimmed-down Sinclair Research on developing an electric bicycle, the Zike, and the A-bike folding bicycle, an electric version of which was launched in 2015. His X-1, another pedal-electric vehicle in a similar vein to the C5, was unveiled in 2010 but failed to reach the market.

In his later years, Sinclair became well-known as a poker player often appearing on Channel 4’s Late Night Poker series. Despite his work in computing, he reportedly did not use the internet or email, finding it a distraction.

He repeatedly expressed grave fears about the future of Artificial Intelligence and how humanity was ultimately doomed if it allowed machines to surpass human levels of intelligence and sentience.

Sir Clive Sinclair is survived by two sons, a daughter, five grandchildren and two great-grandchildren.

Tweet to @ST_Driving Follow @ST_Driving

- After reading about the death of Sir Clive Sinclair, inventor of the C5 pedal-electric car, you may be interested to read all the car makers’ electric vehicle plans

- Read about Hyundai and LG Chem’s battery replacement deal

- An electric car battery heath check system wins innovation prize