Behind the scenes of Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans

His deadly obsession

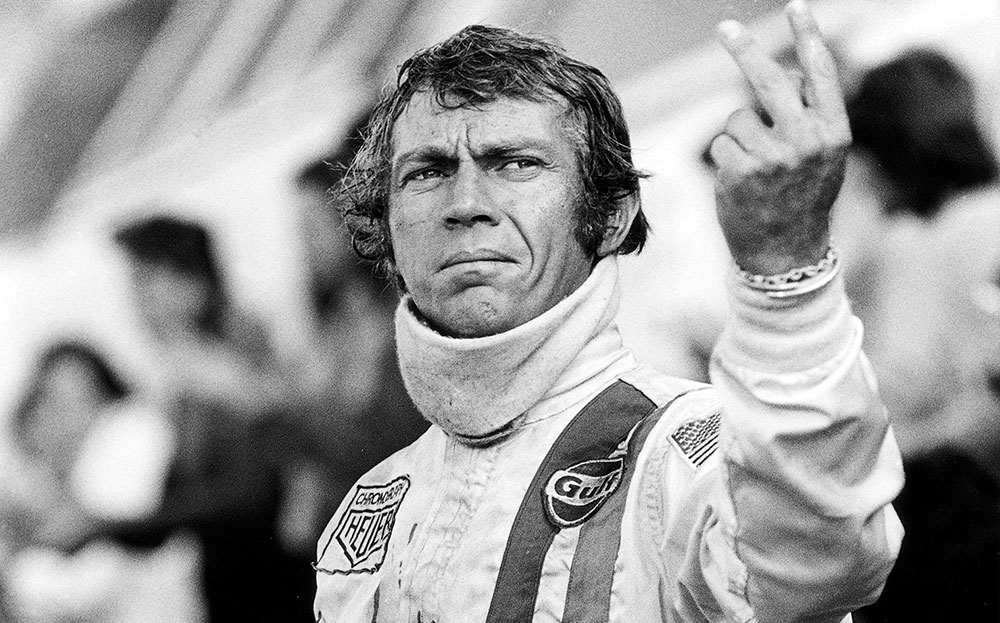

THE YEAR was 1970. Steve McQueen was the king of cool, the biggest film star in the world, with box-office smashes such as The Magnificent Seven, The Great Escape and Bullitt behind him. He was at the top of his game. It was his moment to make the movie that he always wanted to make: an epic about Le Mans, the most exciting, most dangerous and most draining race in the world.

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk

It was a film that would nearly kill him. Wildly over budget, the production was almost cancelled by the studio. The director walked out, the script was unfinished right to the end, McQueen, who had to sacrifice his fee to get it finished, was nearly killed during filming — twice — and another driver lost a leg in a crash. Even after its release the problems continued: it was greeted with lukewarm reviews, and many critics wrote it off as a turbocharged folly — a flawed monument to the ego of its star.

Now a documentary entitled Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans hopes to chart the chaos of what happened when that ego combusted on the racetrack.

Based on previously unseen footage, it interweaves the newly discovered material and McQueen’s private recordings with interviews with many of the surviving production team to reveal the true story of how the film was made. It is already being tipped to be the best racing film since Senna, the award-winning 2010 documentary about the life and death of the Brazilian Formula One champion Ayrton Senna.

“I come from the gutter and I am not a compromiser,” growls McQueen in the documentary, and after 102 minutes of seeing him in action you’ll be left in no doubt about the truth of that.

The documentary is due to premiere this week at the BFI London Film Festival — 45 years after McQueen’s film was made. In that time a mythology has grown up around the making of Le Mans. McQueen’s impossible demands included having assistants drive along the country roads of France wearing racing helmets that he wanted to be covered in insects so they would look authentic. Different numbers of insects were required for different scenes to reflect how much time had elapsed in the 24-hour race.

That very attention to detail means that the film is now regarded as one of the greatest yet made about motor racing. Yes, it has a tangled plot and some dodgy dialogue and is too long, but all is forgiven by fans left breathless by the scenes of cars roaring around the track at 200mph. The temptation for modern film makers to use money-saving special effects, especially CGI (computer-generated imagery), means it is unlikely that a film such as Le Mans will be made again.

“I think he was trying to make the ultimate car-racing film of all time,” says Mario Iscovich, McQueen’s assistant at the time and now a Hollywood producer, who features in the documentary. “Something that was real; something that had never been done before. But some very dramatic things happened.”

Iscovich recalls when he arrived at the set of Le Mans. “It was an empty parking lot, a kind of place where you would envision the circus coming to town. They created a camp — a giant tent for food and bathroom facilities. There were three writers’ trailers — each one contained a writer pounding away — but there was never a completely finished script. The scripts were always being changed, turned upside down — this didn’t work, that didn’t work. It was very disjointed.”

The studio considered shutting down the film but eventually struck a deal with McQueen, in which he gave up his salary, his percentage of any profits and his control

One of the scriptwriters was the highest-paid writer in Hollywood, Alan Trustman, who wrote The Thomas Crown Affair and Bullitt. But McQueen fell out with him and fired him. Trustman barely worked in Hollywood again. The director John Sturges, with whom McQueen had made The Great Escape, walked out in frustration, saying, “I am too old and too rich to put up with this shit.” Sturges had wanted the film to be a love story, with the Le Mans race as the “background”, but McQueen wanted it to be more about the race.

Then there was the budget: McQueen’s production company, Solar Productions, had signed a six-picture deal with Cinema Center Films, which had invested $6m in the movie — the largest budget ever for a McQueen film — but as the months dragged by, the backers started to grow nervous. Eventually Cinema Center Films swooped in on the production (it had not previously been involved in the filming process) and took over completely.

The studio suspended the production for two weeks (even giving Robert Redford a call to see if he would replace McQueen). It considered shutting down the film completely, but eventually struck a deal with McQueen, in which he gave up his salary, his percentage of any profits and his control of the film, in order to get it finished.

“I think he lost it,” Iscovich says. “He went mad in a way: he was trying to create perfection, [but] there was no real rhythm, and no one in the editing room could make sense of it all.

“He was trying to evoke the smell of car racing and capture moments of its purity. This became an obsession and that is what caused everything else to fall by the wayside.

“Everything fell apart.”

The documentary suggests that the disasters on set and the financial problems that plagued the film had more of an effect on McQueen than anyone thought at the time. According to the new documentary, McQueen imagined building a movie empire and taking control of his career as a film maker, not just a Hollywood star, in the manner of Paul Newman. His first step would be Le Mans, the definitive racing movie. The disaster of that film put paid to any such ideas.

McQueen died in 1980. It would be pushing it to say that his film career never recovered from Le Mans — he went on to make The Towering Inferno and Papillon — but according to the documentary, it had a profound effect on the actor. It led to the collapse of his business empire and his marriage.

John McKenna, one of the directors, explained recently: “We spoke to 17 people about what was a huge event in all their lives. One lost his career, another his leg, Neile Adams McQueen her marriage.”

And Steve McQueen? “He lost his opportunity to become the film-producer mogul.”

McQueen contracted a rare form of lung cancer, pleural mesothelioma, caused by inhaling asbestos. When he was racing, he would wear masks that probably contained asbestos. Opinions differ, but it could have been that the thing he loved most killed him.

Steve McQueen: The Man & Le Mans is released on November 20

The meaning of life

“When you’re racing, it’s life. Anything that happens before or after is just waiting.”

So says Michael Delaney, Steve McQueen’s character in Le Mans, when asked why he feels compelled to keep going faster. The line was added to the script at the star’s insistence and has since been reprinted on T-shirts, on posters and in self-help books, becoming one of the most well-known movie phrases of all time.

But the sentiment wasn’t entirely original. McQueen had been inspired by a 1967 magazine article he’d read on Karl “Papa” Wallenda, the German-American high-wire artist who founded the Flying Wallendas acrobatic troupe. “To be on the wire is life; the rest is waiting,” Wallenda had told his interviewer.

McQueen may have been the first film star to spot the resonance of the words but he was by no means the last. Other movies that have appropriated it include All That Jazz (Roy Scheider, on dancing, in 1979), Rounders (Matt Damon talking about playing poker, in 1998) and The Counsellor (Michael Fassbender, on the joys of sharing a bed with Penelope Cruz, in 2013).

Or to put it another way: good artists copy; great artists steal (© Pablo Picasso).

Click to read car REVIEWS or search NEW or USED cars for sale on driving.co.uk