New Chinese vehicle plant in Midlands signals coming of electric black cab

The Chinese car maker Geely is opening a plant near Coventry that will make electric taxis and vans

BRITAIN is to get two new vehicle plants in one. The Chinese car maker Geely has said its new factory in the Midlands will assemble hybrid black taxis and electric vans for shopping deliveries.

Opening the plant at Ansty, north of Coventry, the London Taxi Company, which is owned by Geely, effectively admitted that the plant was a Trojan horse for an investment by one of China’s biggest car companies in the first mass-produced, British-built electric vans.

The plant, about the size of six football pitches, is ready to build more than 20,000 vehicles a year from as early as 2018.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

It will shortly begin building 30 six-seat next-generation black cabs a week. The priority is to get the redesigned TX5 taxi into the hands of London’s cabbies from the end of this year, as new regulations from January 1, 2018, insist that all newly registered licensed cabs must run at least partially on zero-emission technology. But it is understood that the Ansty assembly lines will also produce electric vans for delivery companies such as UPS and Amazon.

The business is moving from its present Coventry home, which is still building the last generation of TX4 cabs. Ansty already employs 600 people and the workforce is expected to reach 1,000 when it reaches full production.

Opening the new plant, Greg Clark, the business secretary, said the factory and its vehicles would help to put Britain at the forefront of the electric automotive manufacturing industry. “We are on the brink of a road transport revolution,” he said. “If people see black cabs go green, they will know all cars can.”

The minister announced that London cabbies would be offered a £7,500 sweetener to buy the electric taxis, which are designed to have a 70-mile range on battery alone, from a £50m fund. That should put the vehicles at least on a par with the price of conventional black cabs, although the London Taxi Company argues that the running costs of hybrid cabs should be much lower. Clark also announced an £18m fund to increase the number of public electric charging points for the taxis.

“If people see black cabs go green, they will know all cars can”

Chris Gubbey, chief executive of the London Taxi Company, said: “This is the first dedicated electric vehicle plant in the UK and the single largest greenfield investment in British automotive manufacturing by a Chinese company.”

Carl-Peter Forster, the chairman, said that the announcement “brings together quintessential British technologies in ‘lightweighting’ vehicles using aluminium and bonding techniques seen in Formula One and in British sports cars”.

Geely, which is putting £325m into the plant, is best known in Europe as the owner of Volvo. Much of the technology for the taxis and vans will come from the Swedish car maker. The electric powertrain will be supplemented by a three-cylinder “range-extender” engine.

London Taxi Company is planning to target markets in Europe, with cities such as Amsterdam, Oslo and Munich all demanding lower-emission taxis.

“The environment could not be better for us in which to launch,” Forster said. “It is the topic of the day.”

Gubbey dismissed the rise of Uber and the like as representing a threat to the conventional black cab. “We have a 100% accessible vehicle for wheelchair users, the mobility impaired, the elderly, the family with a baby and buggy,” he said.

London electric taxi has come full circle

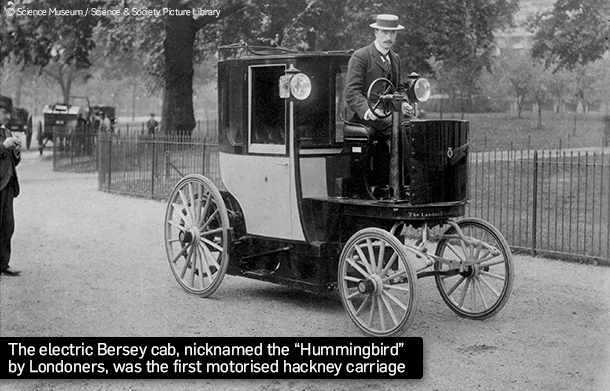

Greg Clark likes the story that the first London cabs were actually electric. Made in 1897 with a top speed of 12mph, right, they were nicknamed the hummingbird for their low drone and garish yellow livery.

They barely made it into the 20th century as they were quickly overtaken by the emerging internal combustion engine, fuelled by cheap, plentiful crude oil.

Now, as the business secretary points out, we have come full circle and Transport for London is licensing only new cabs that run on electricity.

Browse NEW or USED cars for sale

That the new black cab is being built with Chinese money in the historic heartland of the British motor industry is music to the ears of Clark, whose government brief covers Britain’s sputtering industrial strategy. With his energy hat on, he needs to decarbonise Britain; with his industrial strategy bump cap on, he wants to get the country building low-emission vehicles.

The government is said to be standing behind about £80m of the investment. It may need to do much more if Ansty is to become a proper British success story.

Robert Lea, Industrial Editor

This article first appeared in The Times

Growlers and Geelys: a history of London taxis

Additional reporting for driving.co.uk by Will Dron

The first London cabs

Wealthy families who owned horse-drawn carriages began renting out their costly vehicles to less well-off gentry during the reign of Elizabeth I. However, in 1634, the first professional cab rank was established by Captain John Bailey, a regular member of Sir Walter Raleigh’s expeditions, in the Strand. Bailey is believed to have created a uniform for his coachmen, as well as set the fares to charge customers.

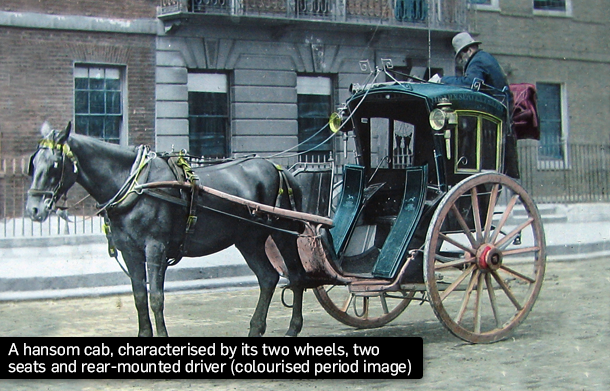

Two types of carriage dominated in the early years: the two-wheeled Hansom cab and the ludicrously named “Growler”, which had four wheels and increased luggage-carrying capacity. The last horse-drawn cab left service in 1947.

The first motorised cabs … and they were electric

Around the turn of the 20th century, motorised vehicles were on the rise, but three propulsion methods were competing for dominance: steam, petrol and electric. At one point, electric vehicles outsold the other two and, indeed, the first motorised London cabs were electrically powered.

The London Electrical Cab Company, established by Walter C Bersey, introduced 25 electric vehicles to London in August 1897. With two seats for passengers, the Berseys, or “Hummingbirds” as they were nicknamed, were smart but heavy (2 tons) and the tyres wore out quickly. Vibrations from cobbled streets proved uncomfortable and damaged the delicate glass plates covering the batteries, breakdowns were frequent and the 12mph top speed was slower than that of horse-drawn carriages. In addition, high electricity prices forced Bersey to build, at great expense, a generation unit to recharge his vehicles. In the end, passengers were disgruntled and the business ran out of money.

Internal combustion prevails

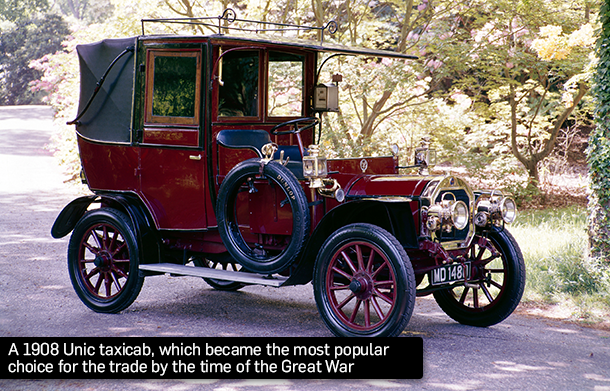

The first petrol-powered London cabs – the French-built Prunel – were launched in 1903. Early British makes included the Rational, Simplex and Herald, but these were available in very small numbers. There were attempts to introduce vehicles from marques recognisable today, such as Vauxhall and Ford, but it was Renault that established a major footing in 1906 with 500 cabs operated by the General Cab Company.

The major player soon became Unic, however, and by the time of the First World War Unic was the only make of “taxi” – a term that came about in 1907 following the compulsory fitting of fare-calculating taximeters (see fast facts below) – still available to buy. The Great War wiped out the taxi trade, however, with drivers called up to fight, while Unic’s factory turned to producing munitions.

Development between the wars

Following the end of the Great War, London’s taxi business took off once more with the introduction of the 1486cc, four-cylinder 11.4 taxicab, made by William Beardmore & Co, a Scottish engineering and shipbuilding conglomerate based in Glasgow. Citroën also got in on the act in 1921, while a Mk 2 Beardmore followed in 1923.

In 1925, a low-cost, two-seat alternative to four-seat taxis was proposed but immediately shot down by the trade. In the end, the Great Depression drove down fares for the larger taxis. It hit the trade hard and by 1927, Beardmore was the only manufacturer still in the game.

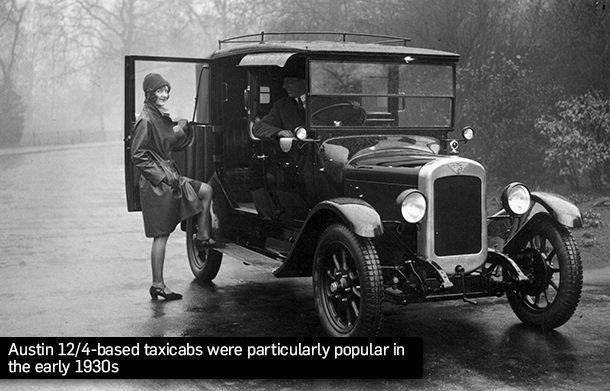

Fortunately, rule changes in the late 1920s soon helped revive the taxi trade, and Morris-Commercial and Austin vehicles began to emerge in the early 30s. The Austin cab, based on the 12/4 and nicknamed the “High Lot”, was particularly successful before a “Low Loader” version appeared in 1934. It became the most common taxi of the decade, before the Second World War crippled the trade for a second time.

The modern black cab takes shape

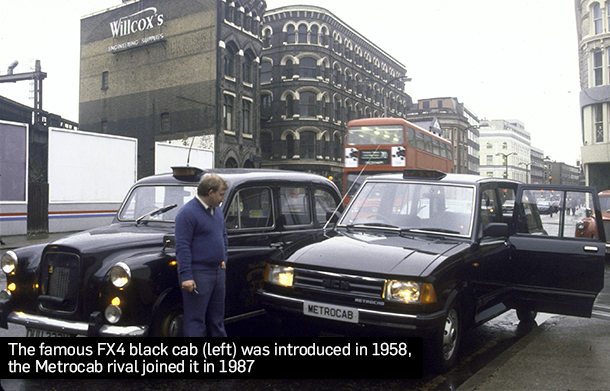

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, taxis such as the Morris Oxford and Austin FX3 really started to influence the shape of London cabs. The Oxford was sold by Beardmore, which hung on in the industry right up until 1966. In the end, it was soundly beaten by Austin following the introduction in 1958 of the famous, and instantly recognisable, FX4. This taxi remained in continuous production, with various modifications and five different engines, for 39 years.

A rival known as the Metrocab was eventually introduced in 1987. It took its diesel engine from the Ford Transit. The Metrocab passed through four owners in 20 years of production and had cornered a quarter of the market by 1997. Demand began to dwindle that year after London Taxis International (LTI) replaced the FX4 with the TX1. This model resembled the classic FX4 but was better furnished and had a new, and very popular, engine from Nissan.

The latest version of the FX4 taxi is the TX4, but its share of the market has been eaten away by competition from big rivals such as the Peugeot E7. Now a new era has dawned in which other major manufacturers are designing their own specialist taxi vehicles (see below). This pushed LTI, which was rebranded as the London Taxi Company (LTC), to the brink of collapse before it was rescued from administration by Geely, the Chinese automotive giant, in February 2013. Production has now restarted and the revived company aims to focus on exports to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates.

Mercedes enters the fray

There is no rule dictating the shape of London taxis but there is a requirement for vehicles to be able to execute U-turns in London’s narrow streets. Most car manufacturers haven’t been keen to develop their existing vehicles around this regulation. However, Mercedes-Benz launched the Vito Taxi in 2008 with rear-wheel steering, allowing London taxi drivers to make the switch.

The Vito Taxi also had six seats for fare-paying passengers and, of course, the premium cachet associated with the German brand. In 2014, 2,177 of London’s 23,000 cabs were Vito Taxis. Mercedes has since renamed the Vito passenger model “V-class”, in line with the nomenclature of its other cars, such as A-class, C-class and E-class.

Nissan’s challenge

In 2014, Nissan launched its own challenge to London taxi dominance with the NV200 Taxi. The vehicle, which was facelifted to fit in with the classic style associated with London taxis since the introduction of the FX4 back in 1958, was approved by Transport for London but the project was suspended over claimed concerns over the proposed ultra low emission zone for the city.

However, the decision to postpone the project raised eyebrows given that Nissan had developed and launched the e-NV200, a pure-electric version that would have met these emissions standards. Due in 2015, it would have reduced by 20% the total exhaust pollution caused by the capital’s 23,000 cabs, Nissan claimed.

Boris Johnson, London Mayor at the time, also backed other forms of electric London taxis, notably an extended-range electric Metrocab from Frazer-Nash and Ecotive, and Geely’s electric FX4-based London black cab project.

London Taxi fast facts

- The “Hackney” of Hackney Carriage is not derived from the area of East London but instead comes from the French word “hacquenée”, meaning a type of horse suitable for hire.

- Hackney carriages are often referred to as “Black Cabs” but there is no rule dictating what colour they have to be. The prevalence of black came about when the FX4 and Oxford taxis were introduced in the late 1940s, and other colours were a cost option. Most professional drivers felt any other colour was a needless expense and, over the following three decades, black became the norm.

- Since 1851, Hackney carriage drivers have been required to study for “The Knowledge”, the stringent test that requires cabbies to know from memory how best to get from point to point in central London.

- In 1823, a two-seat, two-wheeled open carriage known as a Cabriolet was introduced from France. Next time you have a passenger in your drop-top sports car, feel free to impress them with this one.

- The term “taxi” comes from the taximeter, a mechanical device that calculated fares based on distance travelled, or time at a standstill. It was invented by Friedrich Wilhelm Gustav Bruhn of Germany in 1891. They became mandatory for all licensed cabs in London in 1907.