Cars: Accelerating the Modern World — Q&A with curator of new V&A exhibition

'We aren't celebrating the car; we're trying to understand it in a deeper, more nuanced way'

FOR THE last two years, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London has been putting together a new exhibition that explores the contribution cars have had on society.

Cars: Accelerating the Modern World, which opens this Saturday, November 23, is a fascinating and cerebral look at the automobile and its impact on everything from art and design to marketing, manufacturing, travel and the environment.

We caught up with Brendan Cormier, the V&A’s senior design curator, (pictured above with Esme Hawes, assistant curator) to find out more.

Driving.co.uk: Can you describe the exhibition in your own words?

Brendan Cormier: It’s essentially a way of looking back on 130 years of automotive history to unpack how it is that the automobile became one of the most ubiquitous designed objects of the 20th and 21st centuries. We also wanted to explore in surprising and different ways how it had an impact on 20th century society: manufacturing, consumer societies, the environment, and so on and so forth. So it’s trying to look at the car as an agent of change.

D: You’ve said previously that “the car accelerated the pace of progress like no other”. How did it do that?

BC: Many different ways. The car was an interesting invention of the 19th century but for it to become a mass phenomenon, clever people like Henry Ford had to understand how to scale up the means of production. And so it was through the invention of the assembly line that we see modern manufacturers really take on a new kind of scale and pace in the 20th century. And that’s really driven by the automotive industry.

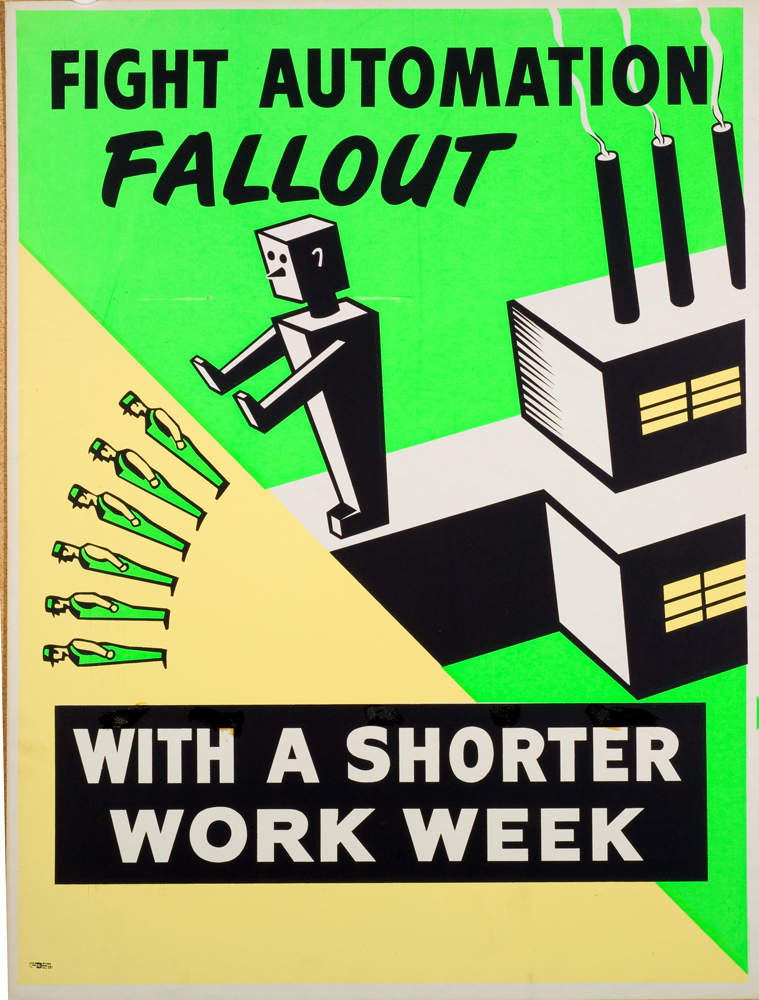

Fight automation fallout with fewer hours of work and no loss of pay poster © Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labour and Urban Affairs, Wayne State University

Fight automation fallout with fewer hours of work and no loss of pay poster © Walter P. Reuther Library, Archives of Labour and Urban Affairs, Wayne State UniversityOf course, we’d had factories before that but the innovations that the automotive industry were developing had a lot of repercussions, and a lot of influence elsewhere. So you see at the beginning of the 20th century, lots of architects and designers being directly inspired by what was happening in automotive manufacture. We explore that to a certain degree.

And that drive to scale up production also pushed the means of automation, so you see robotics really flourishing and taking the lead, as well.

General Motors invented the art and culture section, following in the footsteps of the Paris fashion system … it made you to want to buy a new automobile every two or three years

We also look at the challenge of, once you’ve unlocked the way of making millions of these cars, how do you come up with new means to sell them? One of the biggest mistakes of the [Ford] Model T was that it was one model that lasted for 20 years, and when you had one, you didn’t need to buy another.

So you see innovation, again in Detroit but being led by General Motors, inventing what was called the art and culture section. This was a way of following in the footsteps of the Paris fashion system, to come up with ways of inventing new models every year, creating slight tweaks and changes in order for you to want to buy a new automobile every two or three years, and discard your old one.

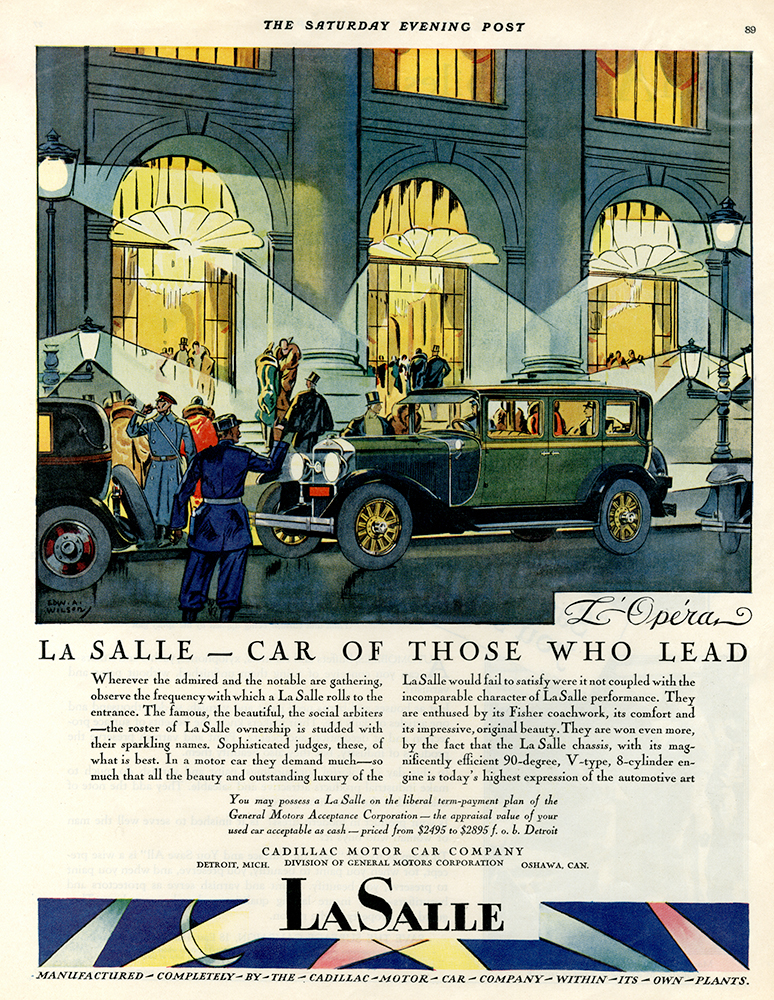

An advert for the GM LaSalle from a series showing the car in various European locations. Illustrated by Edward A. Wilson, c. 1927. © Courtesy of General Motors Company, LLC

An advert for the GM LaSalle from a series showing the car in various European locations. Illustrated by Edward A. Wilson, c. 1927. © Courtesy of General Motors Company, LLCSo again, it’s the automotive industry really leading here, in the ideas of obsolescence, style changes, and the use of colour, that then finds influence in things like early Brownie cameras, typewriters, and other product design. And you can still see it today in modern day smartphones, which every new year come out with a slight tweak in order for us to be compelled to buy more of these objects, when we might not necessarily need one.

D: You’re not saying whether this is a good thing or a bad thing, presumably, you’re just pointing it out.

BC: We try to say it as it is and let the audience make the judgement on that. We don’t want to underestimate the intelligence of the audience to draw their own conclusions from that history. There have been lots of people who have made judgements on that in the past, so it’s all out there for people to understand.

D: It’s particularly interesting in light of the climate crisis and Extinction Rebellion, and the diesel backlash… is now a risky time to be celebrating the car?

C: I don’t think we are celebrating the car; we’re trying to understand the car in a deeper, more nuanced way. In terms of Extinction Rebellion, of course there are a lot of issues that the car industry is facing and reacting to and, obviously, carbon emissions is one of them. One of the things we tried to do in the third section of our exhibition is understand how it is that we ended up with the combustion engine as the main propulsion technology for automobiles.

There’s a really interesting story there, where at the beginning of the 20th century, you had essentially three different propulsion technologies competing with each other: steam power; electric; and then the combustion engine. Steam power was really impractical and dangerous, and so that’s why it didn’t really take off, but electric motors were quite popular. They were being used in races and beating speed records.

Hispano-Suiza Type HB6 ‘Skiff Torpedo’. Hispano-Suiza (chassis) Henri Labourdette (body) 1922. Photo by Michael Furman © The Mullin Automotive Museum

Hispano-Suiza Type HB6 ‘Skiff Torpedo’. Hispano-Suiza (chassis) Henri Labourdette (body) 1922. Photo by Michael Furman © The Mullin Automotive MuseumSo the question is, why did we end up with the combustion engine? Well, there’s a really interesting revelation, which is: if an electric motor can go very fast, what can a combustion engine do? And the answer is it can take you further.

So early car manufacturers trying to come up with ways to build an attraction and a desire for purchasing an automobile really used the idea of the car as a tool for becoming your own explorer. It’s the idea of going off-road, or the road trip, which was really promoted early on. And to do that you essentially needed the use of petrol because electric had the same problem we have today: a range issue — you can’t go that far.

“Why did we end up with the combustion engine? Well, there’s a really interesting revelation”

We show a fantastic project by Citroën in the 1920s, which was just five or six years into their existence as a company, I think, embarking on a marketing campaign where they take these machines called autochenille — which are half tank, half cars — eight of them and they do a trip across Africa. It was a heavily documented trip and they ended up bringing the cars back to the Louvre at the end of it. There’s film, there are objects that they picked up along the way. It was a way of both advertising the power of the automobile to cross what might have been considered at the time the most inhospitable terrain imaginable: the Sahara Desert; the Savannah; through jungle. It was a way to drum up enthusiasm about the power of this newfangled invention to take you afar.

Michelin did the same thing. It invented the Michelin Guide in 1900 in order to sell more tyres. They’re already a successful bicycle company, but they want to move into automotive tyres, though there are only 3,000 registered cars in France in 1900. So they publish 35,000 copies of the Michelin Guide, basically answering, “What can you do with a car?” with, “Well, you can explore all of France at your leisure.” So they built this idea of a tool for going on a road trip, which then, to a large degree, inspires and propels the combustion engine as the leading technology for cars.

So there’s all these curious twists and turns of fate in history that led us to the system that we have today, which we think is really interesting. It’s not that we have what we have today because it’s the best technology at hand; it’s because of marketing, because of politics, and because of entrepreneurs and companies doing what they did.

D: What exhibits do you have, exactly?

BC: We have three sections. The first looks at what was the initial draw and attraction of the car; it was this idea about speed and how the car changed our relationship to speed. Up until that point, we did have in the 19th century a kind of accelerated society. Trains were going very fast, you had the invention of telephony. But what the car did is it put the thrill of speed into the hands of the driver.

There’s this excitement and agency behind driving your own car, which led to a lot of early race culture. And it’s that race culture — which starts at the end of the 19th century and flourishes at the beginning of the 20th century — that starts to drive the rapid advancement of the technology of the car.

General Motors Firebird I (XP-21), 1953 © General Motors Company, LLC

General Motors Firebird I (XP-21), 1953 © General Motors Company, LLCIn the second section, we say okay, if the allure of the car is its speed, the next big challenge is how do you scale up production and bring it to the masses, and that’s where we explore Fordism but also, as I mentioned earlier, the invention of the art and colour section at GM, and how to sell more cars and create a market — drum up the markets of excitement and enthusiasm behind the automobile.

“We have to remember that at the beginning of the 20th century, we had no idea about the environmental impact of these things”

And then in the third section we look at, “Okay, we’ve scaled up production — now there are a billion cars on the planet, what are the implications for space around us?” And that’s where we talk — I think openly and honestly — about the challenges of climate change, but also the early enthusiasm that people had behind petrol.

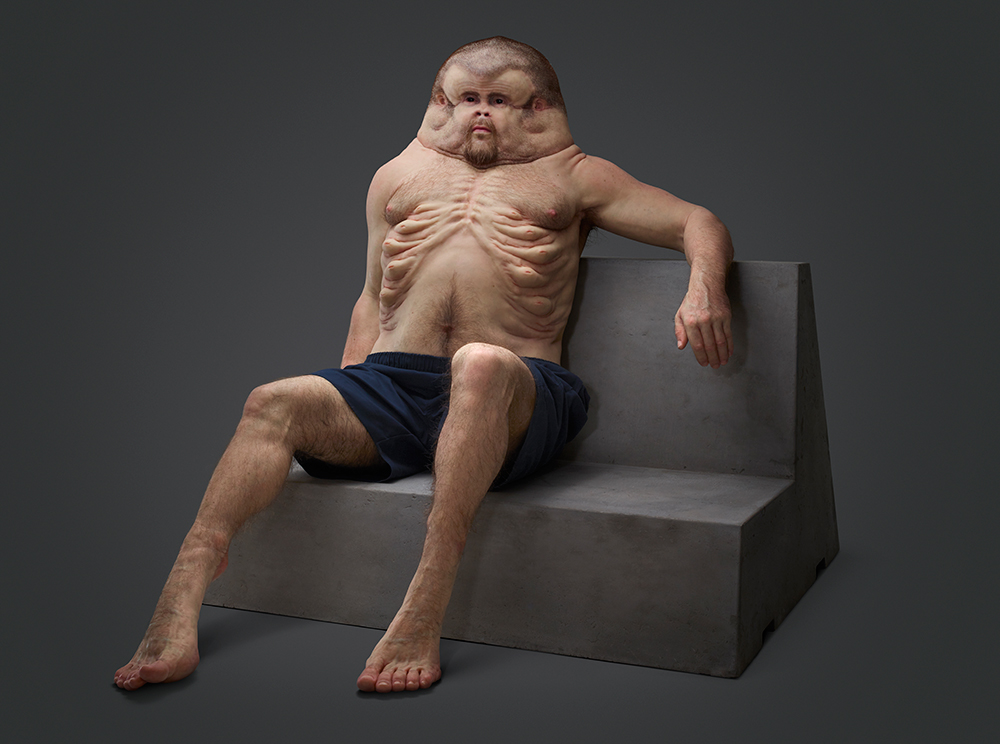

Artist Patricia Piccinini sculpted ‘Graham’ with the bodily features that might be present in humans if they had evolved to survive car crashes, 2016. © Transport Accident Commission

Artist Patricia Piccinini sculpted ‘Graham’ with the bodily features that might be present in humans if they had evolved to survive car crashes, 2016. © Transport Accident CommissionWe have to remember that at the beginning of the 20th century, we had no idea about the environmental impact of these things. That’s what led to a large degree to the promotion of this technology, through massive highway building campaigns — nation building projects like the Volkswagen in Germany — to the Michelin Guides that we talked about, and a kind of proper globalisation of the car at the very end.

D: Are you optimistic about the future of motoring?

BC: It’s really interesting. Throughout the course of doing this project over the last two years, I’ve seen the pace of change go at a much faster rate than I would have imagined. It seems like every day a different car company is coming out with its new electric range — something that I wouldn’t have imagined five years ago. When a company like McLaren is talking earnestly about electric, or when, you know, F1 is talking about becoming carbon neutral — that’s quite an astonishing turn of events in just the past five years.

The Pop.Up Next is a flying car concept from Italdesign and Airbus

The Pop.Up Next is a flying car concept from Italdesign and AirbusD: What do you think will surprise people about the exhibition?

BC: At a top level, people will be surprised to see that the discussions we’re having now about automobiles, whether that be about automation and the future of labour, or whether that be questions about the fuel sources that we choose, there is a long history of discussions about that that have kernels of debate at the beginning or middle of the 20th century. A lot of these things that seem incredibly new to us have actually been embedded within the history of the car for a long time.

Cars: Accelerating the Modern World opens on November 23, 2019 in the V&A’s Sainsbury Gallery. Tickets cost £18.00. Under 11s and members go free. For more information click here.

Main photo © Sarah Weal