Charley Boorman: Potholes? You should see the ones Ewan and I faced in Kazakhstan

A new motorcycling adventure with Charley Boorman and his friend Ewan McGregor airs this week. We sat down with Boorman to discuss the new series, the state of Britain’s roads and why he can’t wait to get back on the bike, even after devastating crashes.

It’s no consolation to anyone who’s recently suffered a punctured tyre or damaged alloy wheel due to a pothole, but the next time you’re cursing the state of Britain’s roads, count yourself lucky that you don’t live in Kazakhstan.

“We’d been given a police escort out of town,” motorcycle adventurer and TV presenter Charley Boorman recalls. “They then pulled over to the side of the road and just waved us on. We went on for another mile or so, and then this road that we were on … it was meant to take a day to get across [but] it took us almost two and a half days. It was a dead straight road through the desert that looked like a runway that had been bombed about 20 times, and it was just all over. There were potholes you’d drive into and you would disappear and come out the other end. I mean, it was extraordinary.

And there were lanes going, you know, 20, 30 tracks either side of the road where people tried to find ways to get across, and they’d been abandoned; trucks just stuck where they got bogged down and broken and just never recovered.”

So, maybe we Brits shouldn’t complain too much?

“Yeah, I think it’s pretty good here.”

Boorman is sitting down with us at his home ahead of the airing of a new series for Apple TV+ in which he and his motorcycling compadre, the actor Ewan McGregor, travel on 1970s motorcycles, from McGregor’s house near Perth, Scotland, through Europe and Scandinavia, to Boorman’s home in the south of England.

Long Way Home, as they’ve called it, follows three other series that kicked off in 2004 with Long Way Round. That first trip covered 9,000 miles, from London to New York City, via Europe, Asia and America. The pair followed that in 2007 with Long Way Down, which saw them journey from John o’ Groats in Scotland through eighteen countries in Europe and Africa, to Cape Town in South Africa.

They donned their helmets again in 2019 for Long Way Up, which made our screens the following year. That ride went from Argentina through South and Central America to Los Angeles in the United States.

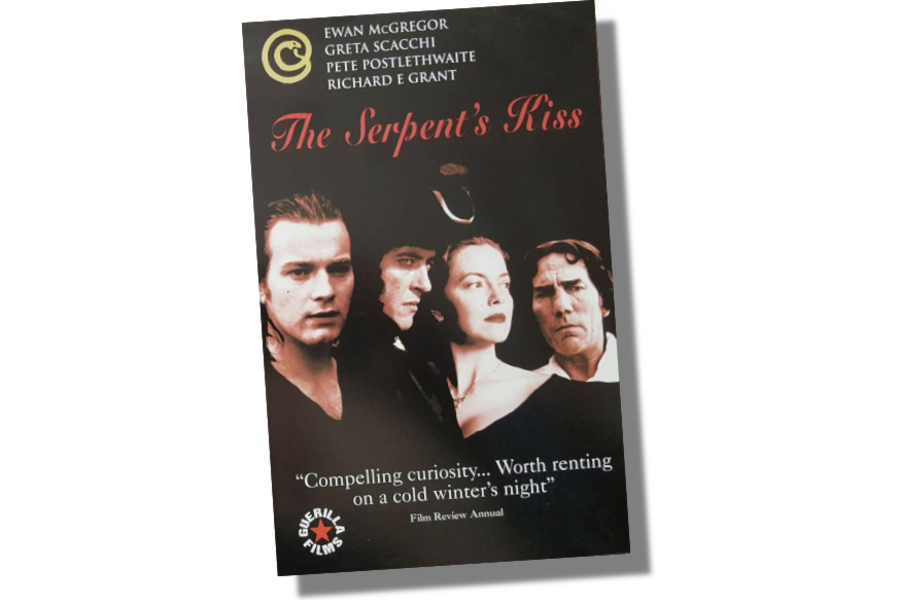

Boorman, the son of film director John Boorman, met McGregor on the set of a movie called The Serpent’s Kiss (1997) and the pair immediately connected over a passion for motorcycles.

“It was my big comeback movie, because I was an actor before I did all this. It was Pete Postlethwaite, Greta Scacchi, Richard E. Grant, Ewan McGregor … and Charley Boorman. And I was like, you know, ‘I’m back.’”

The movie tanked and his acting career didn’t take off as he had hoped, but the experience still changed Boorman’s life forever.

“The film just went straight to DVD but we had a great time, and when I first met Ewan … I went up and said hello to him and said, ‘You’ve got a Moto Guzzi California.’ And he went, ‘Yeah, I love motorbikes, what have you got?’”

The conversation led to a 30-year friendship as well as a joint-owned, championship-winning National Superstock 1000 racing team (a British Superbikes support series), track days together and long weekends away on motorbikes. And then, of course, an idea to go further, in more than one sense.

“We ended up doing Long Way Round,” Boorman says. “I’ve got so much to thank Ewan for really, because my acting career had gone the wrong way, and I’m heavily dyslexic and I was really struggling to learn lines, and I wasn’t enjoying acting anymore; it was stressing me out too much.

“I was getting less and less films and I was doing more and more painting and decorating, and doing people’s houses up, and that was over a 10-year period. It was really hard to realise that your dream of being an actor, and having quite a lot of success, was over. So I was coming to terms with being a builder and I felt I’d let my family down, really, because I wasn’t doing what I said I would do. It was quite a difficult time.”

Then he received a call from McGregor, who’d had a brainwave.

“I went round to his house and he had this big map out and said, ‘Look, I think we should do this.’ And I was like, ‘Okay.’”

Boorman didn’t have the financial means to drop his work and leave his family for four and a half months, though, so came to an arrangement with his colleagues on the newly-formed Long Way production team (which includes filmmakers David Alexanian and Russ Malkin).

“I had five grand in the bank — that’s all I had to my name,” Boorman explains. “I had to make a deal with Russ and Dave and Ewan that I would get a weekly salary, because we didn’t have enough money to pay ourselves.”

A book deal helped finance the trip itself, “After that, I didn’t have anything to lose by going.”

“[It all came about] because of Ewan’s generosity,” Boorman is at pains to point out. “He’s a very kind and generous, nice person, you know — very caring. And I think he realised that…” Boorman’s sentence tails off, though the suggestion is that McGregor had spotted his friend was struggling in more ways than one.

After Long Way Round, Boorman fulfilled a lifelong dream of entering the gruelling Dakar Rally, creating a show about the experience called Race to Dakar. He also made documentaries about motorbike trips from England to Sydney, then Sydney to Tokyo, and another charting a journey that took in the four extremities of Canada.

Long Way Home was conceived as a stark contrast to McGregor and Boorman’s previous trip. Long Way Up was a tricky one to organise and shoot, Boorman says, not only as it involved filming in foreign countries but also because he and McGregor chose to use electric motorcycles: a pair of Harley Davidson Livewires.

“That was a real challenge,” he tells me. “There are no fast chargers in South America, Central America or Mexico, and it was only the last four or five days [in the US] that we had access to them. So it was very complicated. And although it was amazing fun, we lost a little bit of freedom in the fact that we couldn’t just stop and camp on the side of the road, like we had done in the last two, Long Way Round and Long Way Down, and because you always had to plug in [overnight] because there were no fast chargers. It was a little limiting for that.”

Europe and Scandinavia would have been much better suited to electric vehicles, thanks to a more mature charging infrastructure (Norway, in particular, is considered the EV capital of the world, with around 10,000 rapid chargers and almost 90 per cent of new car sales in 2024 being electric). But for Long Way Home, McGregor and Boorman returned to combustion bikes, to avoid any need for compromise.

It also adds an extra element of jeopardy, in terms of the potential for breakdowns, especially as the bikes chosen are around 50 years old. “When you ride these old bikes, you only have an 85 per cent chance of finishing the day,” Boorman says. “So they come with their problems.”

The main reason for choosing them, though, is that McGregor wanted to stretch the legs of one of the favourites in his collection: a 1974 Moto Guzzi Eldorado police bike. “Ewan’s owned it for about 10 or 12 years, and he loves her. She’s a gorgeous, gorgeous thing.”

Boorman had to find something of similar vintage, and settled on a 1973 BMW R75/5.

“I was looking at Ducatis,” Boorman says, “but a lot of Ducatis in those days were quite sporty bikes, and around the mid-seventies they had real reliability issues. So I wasn’t sure what to do.”

A German brand might prove more reliable, he thought, and the he spotted a BMW R75 that had been customised by a specialist for someone else. “It was really nice because the whole front part up to the petrol tank is all original, and then the back, he kind of modernised and made it like a cafe racer. Kind of a retro look, and I really liked the look of it.”

Boorman convinced the owner to sell it to him, and then resprayed it from the original blue to his trademark burnt orange. “I’ve got a quite a thing about orange bikes,” Boorman explains, and that’s clear from a glance around his garage — the collection of bikes includes those from the TV shows, including the orange-hued Livewire used in series three.

There’s also a BMW used during his entry into the 2006 Dakar, which ended prematurely after he crashed and broke bones in one of his hands. Boorman has had a number of accidents on motorbikes, including one in 2016 during which he was clipped by a car, hit a wall and “destroyed” both legs. But that was a small crash compared to what happened next.

“In 2018, I finally got over that [first crash]. I had cages around my leg, and metal everywhere, but I had just got back to riding properly — not walking properly, but riding — and I had a much, much worse one. I just woke up in a hospital in Bloemfontein, in South Africa. I’d snapped my forearm — bent completely backwards, all the bones had come out. I broke my pelvis. I crushed my left side; broke all the ribs, collapsed lung. Head injury, brain swell, brain bleed, massive concussion.”

Boorman says he doesn’t remember the collision itself, just waking up 24 hours later in hospital. According to another account he has given, he has vague recollections of being transported to the hospital in the back of a pick-up truck, pleading for the driver to pull over due to the intense pain.

“That brought the number of operations up to 34 or 35. It has only been since the beginning of last year, 2024, when I started this trip with Ewan, that I’ve been able to walk properly. There’s been a lot of pain.”

Isn’t it difficult to get back on the bike after such devastating accidents?

“It was pretty easy actually,” Boorman says. “The motorcycles were the thing that kept me going — that at some point I’ll be able to get back on a motorbike.

“I think if you ask people who ride horses, or ride motorcycles or bicycles or mountain bikes, or climb mountains — serious people who do it — a lot have probably had serious injuries, and all of them get back on. I don’t know why it just seems like the right thing to do.

“People talk about mental health, and about living in the present and not thinking about the past or, or wishing you were somewhere else or what’s going to happen in the future. You get on your bike and you can only really think about what’s going on at that moment. [It’s about] those bits of decompression.

“If you’ve had a terrible day at work and you’ve got a 30-minute commute, by the time you get home, you feel great because everything’s forgotten. [If] you drive home in the car, you’re still working on the telephone, you’re listening to the radio, you’ve got somebody sitting beside you… you’re distracted. You’re not given that chance. And then you get out the car and you’re walking up to the house and you’re still talking on the phone and kids come and say hello. And you’re going, ‘Shh, I’m on the phone,’ when you shouldn’t be.

“Ewan says it a lot. It really does help your mind, you know. It’s mindfulness. Ever since I was six years old, I’d been doing mindfulness without realising. And I’ll probably hopefully carry on right up to the end.”

That’s great for his mental health, I venture, but what does Boorman’s wife think about it? Is there a conflict between self-care and ensuring that the ones you love aren’t forced to suffer?

He pauses. “The first crash was very difficult,” he admits. “Because it was both legs. It’s very debilitating and it’s a complete change of life. There was a moment where I could have lost my leg. There was a real moment, whether or not we could have kept it. And so she had to go through all of that. And then, to go through another one… you know, she was more pissed off and angry about the second one! She goes, ‘If I have to go down to f***ng get you again, I’m going to f***ing… ‘

“And fair enough, you know. She’s not wanting to, but has to pick up the pieces. And then I go off again.

“But she’s not that bothered. If I spend too much time at home, I see that there’s a suitcase sitting by the door off you go in front of the door.”

Which suggests that, even in their mid- to late-fifties, Long Way Home is unlikely to mark an end to McGregor and Boorman’s motorcycling adventures. Is another series in the works already?

“I don’t know,” Boorman tells me. “I think, like everyone, we get close to the end [of one journey] and we start to talk about another one, because you don’t want to let the one that you’re on end. So, yes, we have spoken about it, but you know, who knows?”

Long Way Home will be available globally on Apple TV+ on May 9.

Related articles

- If you enjoyed this interview with Charley Boorman, you might like to read about the military veteran helping to helping get a Subaru BRZ back on the road… then getting it ready for racing with the Mission Motorsport charity

- The fiancée of a man who died after his motorcycle collided with a car released the accident footage in an effort to prevent similar crashes

- Jim Farley, Ford’s racing driver CEO: Porsche has outsmarted us in the past; now it’s time to outsmart them

Latest articles

- F1 2025 calendar and race reports: The Formula One season as it happens

- Extended test: 2024 Renault Scenic E-Tech review

- Smart #5 2025 review: Not a high five, but the best Smart for years

- BMW iX xDrive45 review 2025: Divisive looks remain but updated electric SUV is otherwise superb

- Aston Martin Vantage Roadster 2025 review: Still hardcore but with added pose factor

- Updated Skoda Enyaq vRS matches 0-62mph time of Czech firm’s fastest-ever car

- Long Way Home review — Ewan McGregor and Charley Boorman hit the road again

- ‘I was a tear-soaked mess’ — Richard Hammond opens up on his last Top Gear show during new race with James May

- Charley Boorman: Potholes? You should see the ones Ewan and I faced in Kazakhstan