The Times archive unearths story of the first UK in-car radio trial from a century ago

Tony Blackburn was not involved, we understand

Almost exactly 100 years ago, a technology trial by a leading German car maker and a British telecommunications firm sowed the seed for the advanced in-car audio systems we now take for granted.

Last week The Times newspaper published one of its articles from October 1922, in which Daimler and Marconi were reported to have set up a joint venture to introduce “wireless concerts” into cars as they were being driven.

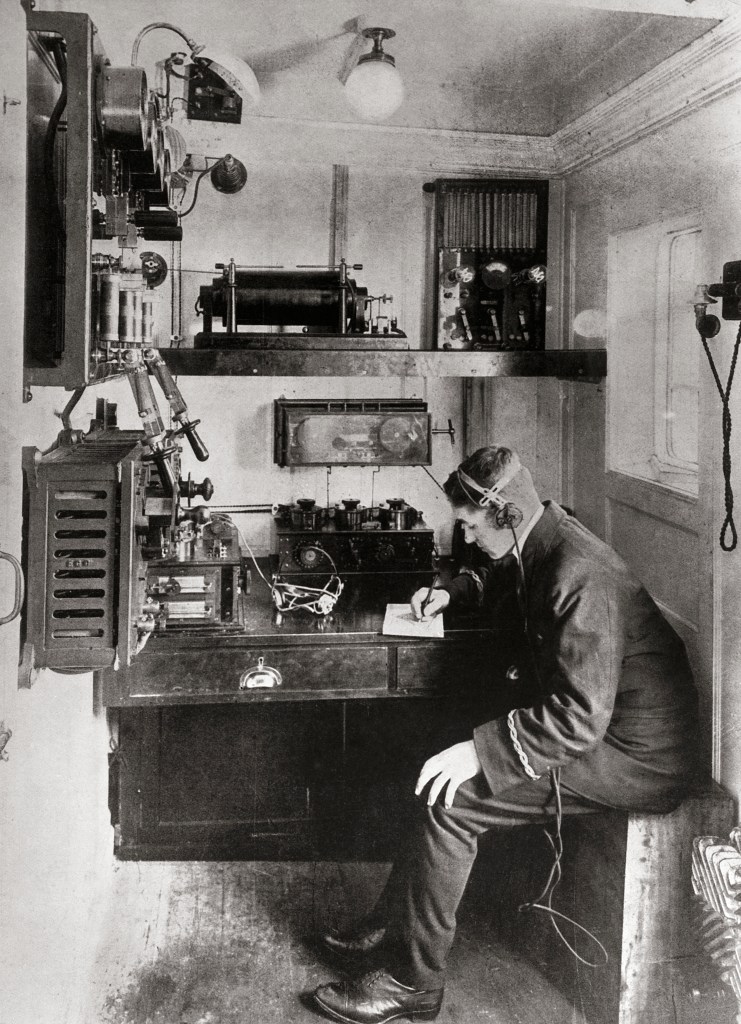

Guglielmo Marconi, an Italian, had proven that radio waves could be transmitted long distances and thereby used as a messaging system, and by the turn of the century Marconi was able to transmit across the Atlantic ocean. In 1909 Marconi and Karl Ferdinand Braun were awarded the 1909 Nobel Prize for Physics for their developments in “wireless telegraphy”.

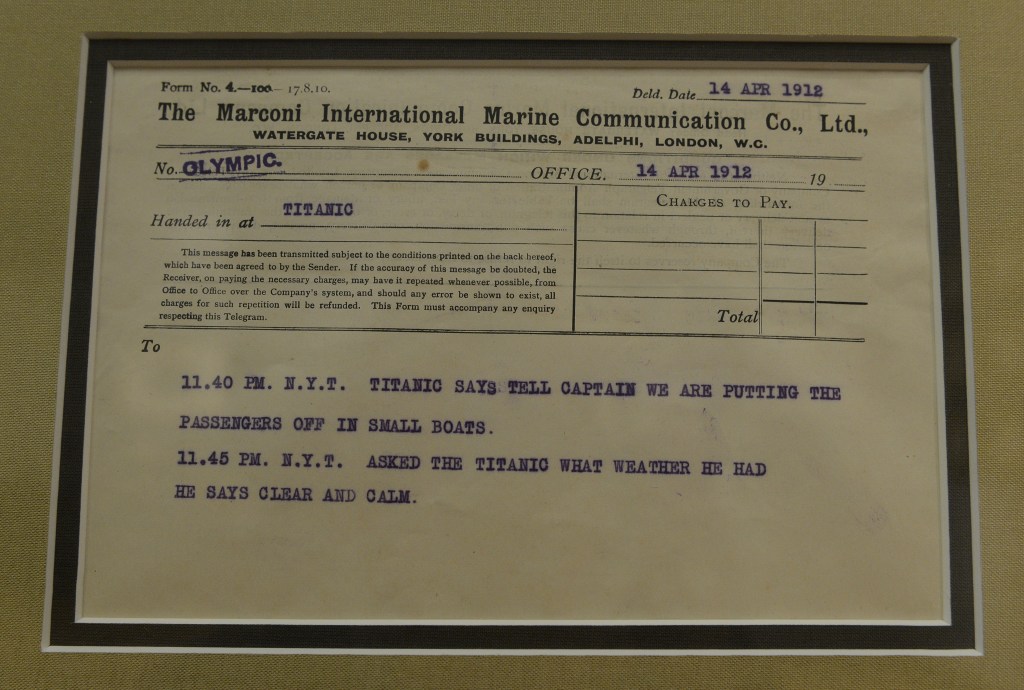

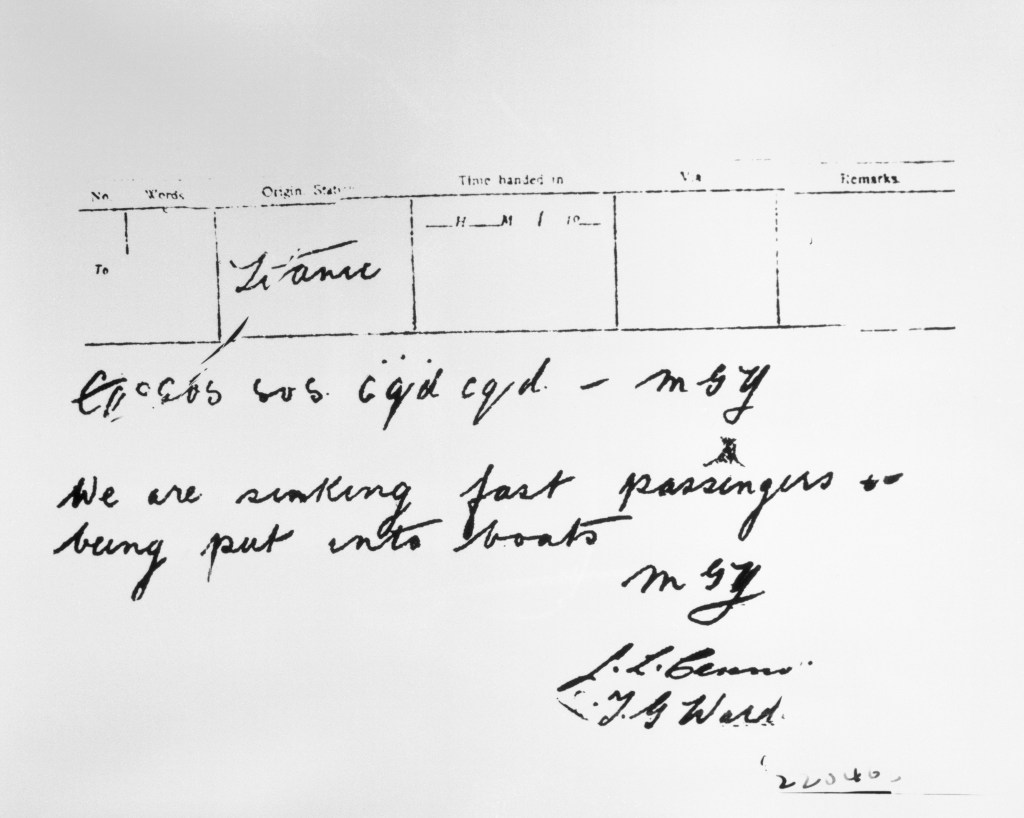

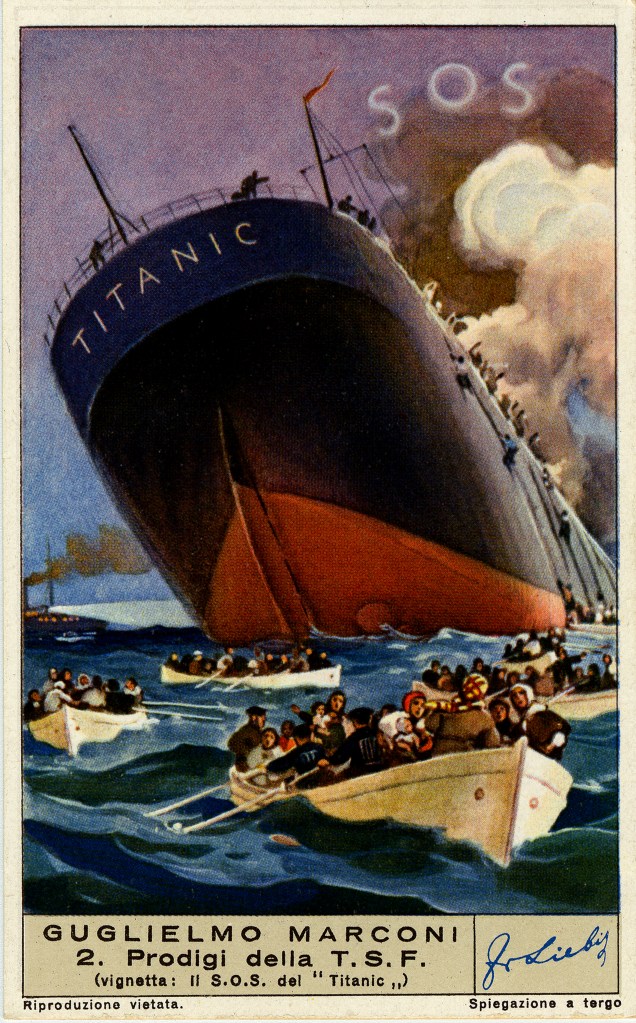

The sinking of the Titanic in 1912 brought greater notoriety to Marconi, as its radio operators were employees of his company, not of the White Star Line that owned the ship itself, and it was their SOS messages that alerted the RMS Carpathia to the Titanic’s sinking, and allowed them to change course towards the disaster. Marconi’s radios were credited with saving the lives of the survivors.

But it took another 10 years, following the First World War, for car makers to get involved, and it was Daimler that first realised the potential of allowing its customers to tune into radio broadcasts while on the move.

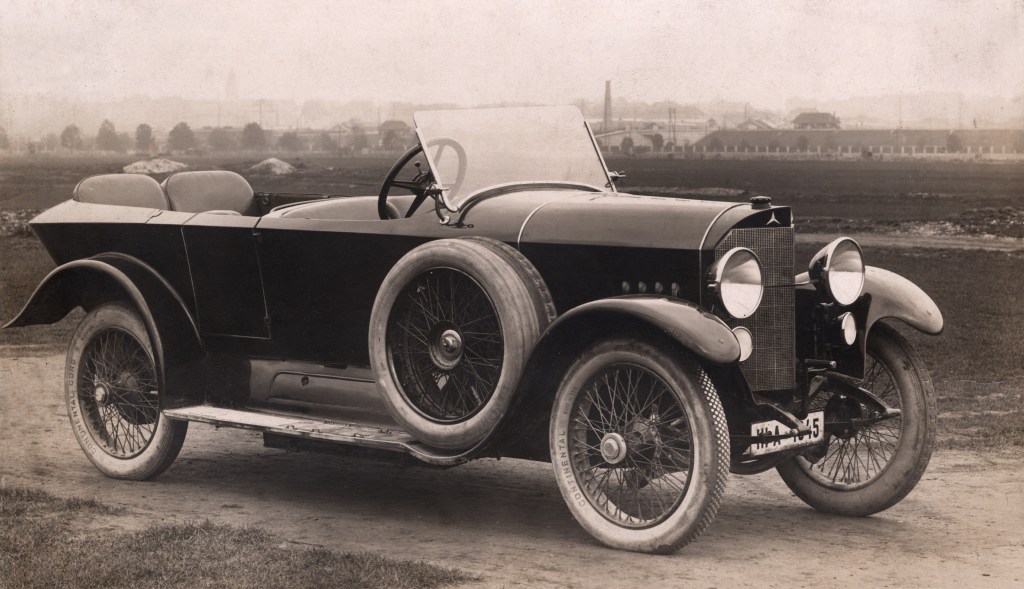

Pictured below is a Daimler Mercedes 10/40/65 hp from 1922 — the sort of car that may have been involved in the trials. However, the two cars took in the London experiment were both closed-topped and fitted with large aerials, and inside was receiving equipment bulky enough to take up the same room as a passenger.

And to hear the transmissions, occupants had to use “ear telephones”, though it was understood even then that loudspeakers could be integrated into the vehicles themselves.

Today we have connected cars with multiple speaker set-ups and able to access to digital radio stations, and drivers can use voice commands to stream any song they desire over high-speed 5G networks (what would Marconi think of that, we wonder), but it was these early “wireless” experiments that sparked the revolution in in-car entertainment.

From The Times: October 25, 1922

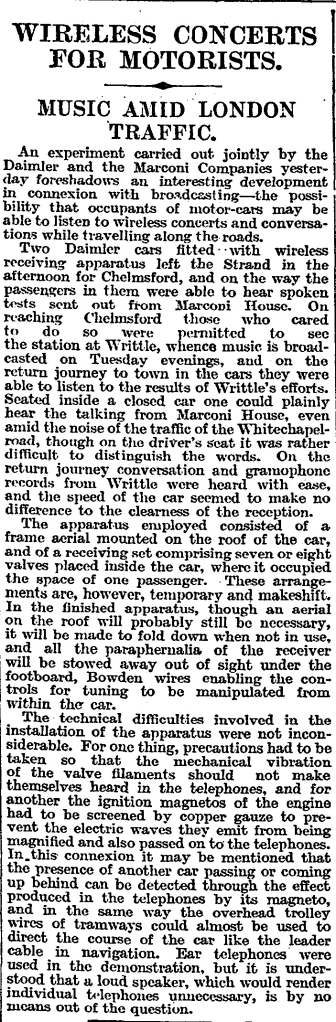

An experiment carried out jointly by the Daimler and the Marconi Companies yesterday foreshadows an interesting development in connexion with broadcasting — the possibility that occupants of motor-cars may be able to listen to wireless concerts and conversations while travelling along the roads.

Two Daimler cars fitted with wireless receiving apparatus left the Strand in the afternoon for Chelmsford, and on the way the passengers were able to hear spoken tests sent out from Marconi House. On reaching Chelmsford those who cared to do so were permitted to see the station at Writtle, whence music is broadcasted on Tuesday evenings, and on the return journey to town they were able to listen to the results of Writtle’s efforts.

Seated inside a closed car one could plainly hear the talking from Marconi House, even amid the noise of the traffic of the Whitechapel Road, though on the driver’s seat it was rather difficult to distinguish the words. On the return journey gramophone records from Writtle were heard with ease, and the speed of the car seemed to make no difference to the reception.

The apparatus consisted of a frame aerial mounted on the roof of the car, and of a receiving set comprising seven or eight valves placed inside the car, where it occupied the space of one passenger. These arrangements are, however, temporary and makeshift. In the finished apparatus, though an aerial on the roof will probably still be necessary, it will be made to fold down when not in use, and all the paraphernalia of the receiver will be stowed out of sight under the footboard, wires enabling the tuning controls to be manipulated from within the car.

The technical difficulties involved in installing the apparatus were not inconsiderable. For one thing, precautions had to be taken so that the mechanical vibration of the valve filaments should not make themselves heard in the telephones, and for another the ignition magnetos of the engine had to be screened by copper gauze to prevent the electric waves they emit from being magnified and also passed on to the telephones.

Ear telephones were used in the demonstration, but it is understood that a loud speaker, rendering individual telephones unnecessary, is by no means out of the question.

Explore 200 years of history as it appeared in the pages of The Times, from 1785 to 1985: thetimes.co.uk/archive

Related articles

- If you were interested in this Times Archive story from 1922 about Daimler and Marconi’s wireless radio tests, you might be interested in this story about the expansion of DAB across Britain in 2018

- You might also like to read this Classic Clarkson review of the 2012 Porsche 911, which he awarded zero stars

- And take a look at this 2018 Me and My Motor interview with Justin Webb, the BBC Radio 4 Today programme presenter

Latest articles

- New electric-only Mini Aceman fills gap between Mini Cooper hatch and Countryman SUV

- Tesla driver arrested on homicide charges after killing motorcyclist while using Autopilot

- Porsche Macan 2024 review: Sporty compact SUV goes electric, but is it still the class leader for handling?

- F1 2024 calendar and race reports: What time the next grand prix starts and what happened in the previous rounds

- Aston Martin DBX SUV gets the interior — and touchscreen — it always deserved

- Nissan unveils bold look for updated Qashqai, still made in UK

- British firm Bedeo launches new EV conversion kit for classic Defender

- New Citroën C3 Aircross gets electric power and up to seven seats

- Maserati GranCabrio Folgore is a 751bhp droptop luxury EV